As I said in the prior post, this series is for two types of companies: (1) those that are merely dipping their toes into mHealth because they’re afraid of the water, and (2) those that are diving right in head first with no idea how deep the water is. Both types of companies might be making mistakes, either by letting good opportunities go by or by incurring undue regulatory risk. I’d like to convince both types to be more measured and informed in their approach to mHealth.

In the first post, I laid out all the nasty stuff that can happen if you enter mHealth and your app or your hardware ends up FDA regulated, but you don’t comply. That post was ugly, but it had to be done, because it laid the groundwork for this post. Now I’d like to share the good news that there is plenty you can do to mitigate your risk of FDA enforcement. As usual, I think in lists. The following is my checklist.

1.Check your attitude. I’ve been doing this for almost 30 years now, and I can generally tell which companies will succeed and which will fail when it comes to FDA compliance. There is one very clear hallmark of the companies that succeed—in their attitude they are able to embrace the FDA and put patient safety first. If you can do that, you’ve won easily half the battle. It sounds almost silly, but it goes to the very DNA of the organization. If the organization views FDA as a stakeholder that needs to be kept happy, they will organize their business partly around pleasing that stakeholder, in addition to customers, shareholders, employees and others. These companies make it part of their mission to learn the rules and play by them. If you can’t do that, my advice is simple. Stay out of this space.

2.It’s all about intended use. In prior posts, I’ve tried to explain the concept of intended use. As you might recall, intended use is the manufacturer’s objective intent with regard to how its customers will use its product. This concept is the linchpin of FDA regulation. It determines everything, including (1) whether or not FDA regulates your product, and (2) if it’s regulated, to what level. Intended use is therefore by far the single biggest determinant of regulatory risk, and companies that figure that out put in place robust systems for managing the intended use of their products. That means they carefully manage how they promote the products and what design features they add. They tightly control all of the things which ultimately determine the company’s intended use for their product, so that it stays exactly where they wanted it to stay.

3.Aim as low as you can. To reduce regulatory risk, focus on the lowest risk conditions and the least claims you can make. The risk associated with the health conditions you target partly determines the regulatory category (it’s an element of the intended use), and the claims you make about your product need to be proven to FDA’s satisfaction. So I say, aim as low as you can. I can almost hear the marketing people screaming. Okay, I get it -- you need to be bold in business to make money. So what I’m really saying is pick a happy medium between the “our product will save the world” claims the marketing people want to make, and selling an inert paperweight. Carefully pick whatever the least is that can accomplish your sales goals. Less can definitely be more. Further, many companies not traditionally in the healthcare space confuse “common” with “low” risk. Diabetes is quite common these days, but not low risk. Similarly, claims of real time monitoring of patients with serious conditions are not low risk. Learn the difference.

4.Pursue a generic intended use. You don’t always have to tell people exactly how to use something. I can make and sell test tubes without regulatory oversight so long as I’m just making a glass tube and the claims I make relate, for example, to the quality of the glass and its cleanliness. I can make a network router that is just a router. Where I tend to get put in the regulatory soup is when I start to make specific medical claims that, for example, my router is especially good because of its design for some specific medical application. For the generic intended use strategy to be legitimate, there have to be legitimate nonmedical uses, which for test tubes and routers is not a problem. Please remember, though, how broad the concept of intended use is, in that it encompasses, for example, (1) the words I use to describe the product, (2) any special design features I might add that have only medical uses, as well as (3) uniquely medical channels of distribution I choose to pursue.

5.Take a more nuanced approach. It’s not all in or all out. There are many different roles the company can play in the industry. Companies can avoid many of the regulatory obligations by limiting their role to serving as a contract manufacturer. Or a design firm can collaborate with the manufacturer without taking on all of the regulatory obligations. Or you can just be a distributor of someone else’s willing to be the manufacturer. There are lots of roles to play, they aren’t all equally risky. I explained that in excruciating detail in a prior post.

6.Manage your supply chain well. The most successful folks I know in the medical device industry would put this at the top of their list, as a matter of general business practice. It makes my list with regard to ensuring regulatory compliance for several specific reasons. Companies should get accustomed to using supplier contracting to share the burdens of regulatory compliance—asking their suppliers to shoulder some of the obligations. At a minimum, contracts should specify the regulatory obligations rather than leave the issues unaddressed. Warranties are important, and there is even a so-called “pure food and drug warranty” in the FDA regulations which if you use that wording you can shift regulatory risk upstream. There also are whole tasks that can be outsourced, notably the clinical research function to a Clinical Research Organization. This is a little bit controversial in the device area; there’s an express provision on the drug side of FDA that allows this but not so on the device side. Even so, using a CRO typically can help reduce the risk.

7.Build a robust compliance infrastructure. You’re probably thinking, wow, what great insight he has. Well, I couldn’t exactly leave it off the list even if it’s perfectly obvious. And frankly I don’t want to attempt to thoroughly cover the compliance process—whole books have been written on that. Instead, let me just say that compliance tends to depend very heavily on having written procedures, documenting compliance, and training your people. It requires a continued investment to control your organization that includes in equal measure auditing to find noncompliance and fixing what you find. It’s funny-- some companies are really good at auditing and not very good at fixing. Other companies are not so great auditing but they do fix what they find. Frankly it takes both, in a sustained way.

8.Control your communications. Once companies figure out that intended use impacts regulatory risk, and that they need a very proactive compliance program, they generally implement an intense program to control communications. At many science-based non-medical companies, the scientists are encouraged to engage in discussions rather freely. That doesn’t work very well in the medical device space. But even more importantly than the scientists, companies target communications that create impressions in the marketplace with regard to the intended use of their products. In this regard, companies learn that what they put on their website really matters, because in this era of limited resources, FDA makes disproportionate use of visiting websites to gather evidence for enforcement. Equally so, companies control what they say at trade shows because FDA attends those shows to efficiently learn what everyone in industry is saying. Further, emails can be rather dramatic evidence of a company’s intended use for its products. So companies train their people to stay within fixed parameters when describing intended use in email, just as in any other communication. When you are regulated by FDA, what you say really matters.

9.Run a tight ship. Operations plays a big role in regulatory compliance, particular because product quality is such a central focus of FDA regulation. The companies I’ve seen that have been most successful aspired to meet very high quality standards. I want you to understand that I chose the word “aspire” very carefully just then. I selected it instead of, say “set” high quality standards, because a company should not self-impose through policies an extremely high quality standard beyond what FDA would require. The reason is simple -- you can hang yourself by not meeting your own standard. So companies that document reasonable standards and then push their people to always in practice aspire to the highest quality do the best. After all, high-quality products generally mean you won’t have customers complaining or people getting hurt, and therefore you are less likely to have FDA knocking at your door. As I noted in the first post, the practical reality is that FDA goes after public health risk, so if you don’t create a public health risk, you stand a better chance of avoiding FDA enforcement. In addition, documenting what you do should become part of the DNA of the company. In FDA’s view, if it’s not documented, it didn’t happen. So the practice of documenting actions has to get woven into every day operations in an efficient and effective way.

10.Invest in recall preparedness. Sorry to be the bearer of bad news, but if you end up in FDA regulated space, you need to be prepared for recall. It will happen. They are a common fact of life. If you put regulated software or hardware out onto the market and it doesn’t work the way it should, FDA’s going to expect you to recall it. The good news is that there are techniques you use in your operations that will make it far easier to efficiently identify and quarantine the scope of what needs to be recalled, and then recall it efficiently. But it takes prior planning. There are many consultants and vendors out there who can help companies put in place systems to make recalls less painful. Recalls will never be pain free, but with prior planning the pain can at least be minimized.

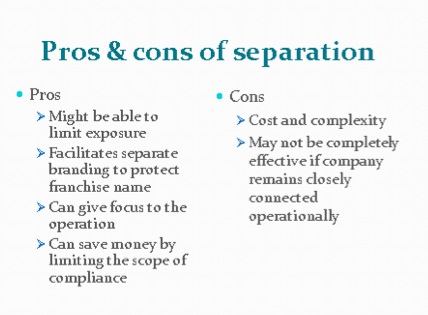

11.Consider setting up a separate health business. Without trying to be pejorative, think of FDA regulation as a virus that needs to be contained. Then think through how best you can use corporate structures to limit the scope of FDA regulation on your operations. In tandem with creating separate corporate forms, you will need a relatively clear delineation between those operations subject to the quality system, and those that are not. In addition to limiting regulatory risk, this separation might also be an opportunity to limit reputational risk to your brand. In the table below I have sought to outline some of the pros and cons of creating a separate corporate structure to own and operate the medical device operations.

If you decide to pursue this, though, be aware that separation might prove to be complicated. One of the most heavily regulated aspects under the quality system is the design control process, but figuring out how to separate R&D in a meaningful way might be difficult. Generally, the research side would not need to be separated, but the development side would. Further, just like any divorce, you have to separate the assets including the plant, equipment, intellectual property and records. All of the records associated with the quality system must belong to the medical device corporation. In addition to assets, the actual manufacturing processes will need to be separated. It is possible though, to use one company as a contract manufacturer for the other, but that means the contract manufacturer is subject to the quality system. People and governance need to be separated, keeping control at the strategic level without destroying the separation. If the separation is not sufficient, the regulatory requirements could carry over to the mother ship.

12.Get good help. Well, duh. This has always been a rule of business, but it is particularly important here. You need to get good advisors and vendors with regard to medical device compliance matters including submissions to the FDA and any clinical testing that you need to do, among other things. You can also reduce your risk by getting second opinions by outside attorneys and consultants, but you need to realize that those opinions do not constitute a get out of jail free card. You still have ultimate responsibility. All the opinions do is make it more likely that FDA will respond to you with at least some sympathy. The companies you partner with, including critical areas like the design process and manufacturing, can have a big impact on your regulatory risk if you are the entity that bears that risk. So get good help, and use appropriate due diligence to make sure that all of your advisors and partners can perform to the levels needed.

13.Work with FDA. The very first item on this list was to challenge you to critically self-assess whether you can treat FDA as a strategic partner. So assuming you can do that, you need to start building a relationship with the agency and lines of communication. If you find yourself involved in advocacy, make sure that you’re advocating policies that are sensible for patients as well as innovation. Remember, everything we do is about the patient. Generally, if you plan to consult FDA, consider doing it early when you have the most flexibility to adapt and to give them time to think about it. Also, seek clarity, but not too much. Some people just can’t stand ambiguity, so they will over communicate with FDA to try to pin down even the smallest details. I don’t recommend that. When you do that, you have to realize you will get the most conservative advice each time, plus eventually they will get annoyed. They are not your consultants-- they are too busy to field every question. Sometimes taking a good faith, informed position is the best in the face of ambiguity. If FDA raises questions about your compliance, treat them right. Always be respectful, be prepared for surprise inspections and take any warning you receive seriously. It’s really not that hard, but it needs to be part of your DNA.

14.Watch out. Vigilance in this industry is essential. Watch your competitors. If they go through the FDA compliance process, you can be darn sure they will expect you to, and will complain to FDA if you don’t. Watch out for changes in the law, regulations and FDA sentiments. This is an area that changes constantly. Subscribe to the right journals, monitor the right websites and attend the right meetings. It’s terribly important to stay up-to-date on the regulatory environment.

15.Be proactive. Indeed, this is the main point I’m trying to make. Confront the issues directly and intelligently, rather than just hoping they go away. Don’t just assume that compliance will happen so long as you’re a good person. It’s doesn’t work that way. It takes a lot of affirmative effort.

This probably sounds scary, and it is a bit. But realize that there are roughly 20,000 companies registered with FDA as medical device manufacturers, and about 80 percent of them qualify as small manufacturers. If they can do it, you probably can too, if you really want to. Often the rewards are well worth it. But it’s up to you.

To get MobiHealthNews in your newsfeed, Like us on Facebook.

By

By