Is the placebo effect real even without the deceptive element of making people believe they are receiving a pharmaceutical treatment? One entrepreneur thinks so, and is looking for like-minded people to back him in hopes of bringing a mobile app to market this summer.

Is the placebo effect real even without the deceptive element of making people believe they are receiving a pharmaceutical treatment? One entrepreneur thinks so, and is looking for like-minded people to back him in hopes of bringing a mobile app to market this summer.

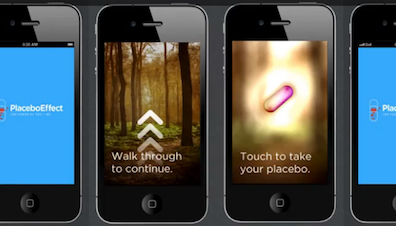

A Seattle-based startup called Placebo has developed an app called Placebo Effect that is intended to help people feel better about themselves and to sustain behavior changes such as quitting smoking simply by mentally transporting them to someplace positive — akin to meditation or hypnosis.

"This is not a complex thing," company director Daniel Jacobs tells MobiHealthNews. "It's something that touches people's hearts."

Jacobs trying to raise $50,000 through Indiegogo to commercialize the app. In a video on the Indiegogo site, Jacobs calls Placebo Effect the "world's first placebo mobile application."

As of Wednesday afternoon, he had secured nearly $8,700 in crowdfunding pledges from 63 sources, including the Szollosi Healthcare Innovation Program, with 20 days until the June 3 deadline.

"This will be on the market fairly quickly, almost certainly in the next two months," Jacobs promises. The first Placebo Effect release will be an Apple iOS app, but should the company exceed its funding goal, Android and Web versions should follow in short order, he says.

Jacobs says that his team, which includes former Gates Foundation IT director Paul King and NBC Entertainment executive Jeff Bader, has not determined the company's marketing strategy yet, but the choice is between partnering with employers and health plans or going direct to consumers. "One way or another, there will be a consumer element," Jacobs says, since the plan is to make the mobile apps available through the iTunes App Store and Google Play.

Similarly, Jacobs is not ready to announce the app's price.

What he is eager to discuss is the "personalization" of the placebo effect and to debunk the notion that deception is a necessary component. Jacobs says the idea of deception has been in wide use since 1955, when Dr. Henry K. Beecher introduced the notion of double-blind studies in pharmaceutical research. But, as Beecher himself noted, the word "placebo" has been around since the early 19th century to describe "medicine given more to please than to benefit the patient."

According to Jacobs, "Deception is not necessary when people take placebos." Recent research has supported this statement, such as one finding that Jacobs likes to cite that shows placebos have about 75 percent the effectiveness as antidepressants in treating mild to moderate cases of depression.

Occasionally, Jacobs says, placebos can be more effective than medical treatment, such as in patients who genuinely hate seeing doctors.

Of course, some in the healthcare industry will dispute these claims, and the idea remains controversial. Jacobs noted that pharmaceutical companies would not be so eager to run trials on placebos outside the framework of the double-blind study.

The Placebo Effect app lets users "personalize" the placebo by asking a series of simple questions. For example, people who want to feel happier are asked, "Who's the best person to bring me joy" and, "What's the best place to find joy?" (In testing of a prototype iPhone app, Jacobs reports that few people said their doctor brings them joy and none looked for happiness in a hospital.)

They then are asked to select a placebo image, with choices including a pill, herbs, a Bible and a magic wand, though users can pick their own image. About 12 percent of test subjects chose the pill, according to Jacobs. "A placebo isn't a thing. It's a transformational symbol," he explains.

Jacobs says his company will not build hardware, but is looking to partner with others that do — perhaps including heart and blood-pressure monitors — to bring physiological data into the Placebo Effect app. "That kind of stuff is real exciting to us," he says. "Those are natural partnerships for us."