I. Scientific evidence mounts for the importance of sleep

Like most areas of digital health innovation, one of the main things driving the trend of sleep medicine innovation is the availability of new technologies. Wearable, connected sensors can measure activity, heart rate, respiration, and even brainwave activity, which together can produce a pretty accurate picture of how someone is sleeping.

Like most areas of digital health innovation, one of the main things driving the trend of sleep medicine innovation is the availability of new technologies. Wearable, connected sensors can measure activity, heart rate, respiration, and even brainwave activity, which together can produce a pretty accurate picture of how someone is sleeping.

But there is a second driving force behind new technology for monitoring sleep: scientific evidence continues to mount of the various negative health outcomes that can stem from lack of sleep or irregular sleeping patterns. Recent studies have suggested that poor sleep could affect metabolism and weight gain, can contribute to mental health conditions like depression, can effect memory, cognition, and day-to-day performance, and can even increase the risk of cancer.

A December 2010 study from Harvard Medical School put the costs of undiagnosed sleep apnea at $65 billion to $165 billion a year, taking into account medical costs, lost productivity, and traffic and work accidents caused by sleep apnea.

Sleep health and cognitive performance

It's probably no surprise to anyone who has experienced sleep deprivation that losing sleep can affect cognition, and a building body of research supports this. Just this month, a study in the Journal of Developmental Psychology showed that optimal sleep efficiency improved attention and processing speeds in lower income school-age children.

And it's not just children -- a study last fall in the Journal of Sleep Research showed that in adults aged 50 to 91, getting more REM sleep (rapid eye movement, the deep, restorative part our sleep cycle) led to better performance on verbal learning, visual attention and verbal fluency skills. They also found that spindle density, a marker of how much REM sleep someone gets, increased in older patients, suggesting that sleep degradation might play a role in the cognitive decline associated with aging.

One recent study by Australian researchers illustrates the point very well: they found that simulated driving with 18 hours of sleep deprivation was on par with simulated driving with a blood alcohol level of 0.05, and 24 hours of sleep deprivation was equal to 0.10 BAC -- above the legal limit.

Recent studies have tied sleep closely to our ability to form new memories and recall old ones. Sleep seems to be the time our brains engage in "memory consolidation," which is essentially the process by which short term memories become cemented into long-term memories. Disrupted sleep can impair this process.

There's also a link that's been shown in various studies between sleep and particular mental illnesses. In fact, an editorial in the May issue of the journal European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry called the association between sleep and mental illness "overlooked and underappreciated". Links have been found between disruptive sleep and depression, bipolar disorder, and suicidal ideation. The causal relation seems to be complex -- recent studies have shown gene links between propensity for bad sleep and mental illness. But even if the mental condition causes lack of sleep and not the other way around, the writers in ECAP posit that sleep therapy could be an effective treatment tool for some of these conditions.

There's also a link that's been shown in various studies between sleep and particular mental illnesses. In fact, an editorial in the May issue of the journal European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry called the association between sleep and mental illness "overlooked and underappreciated". Links have been found between disruptive sleep and depression, bipolar disorder, and suicidal ideation. The causal relation seems to be complex -- recent studies have shown gene links between propensity for bad sleep and mental illness. But even if the mental condition causes lack of sleep and not the other way around, the writers in ECAP posit that sleep therapy could be an effective treatment tool for some of these conditions.

A massive twin study in the journal Sleep, published this year, showed that in patients with a genetic predisposition toward depression, those who slept seven to nine hour a night we're significantly less likely to have depression symptoms than those who slept more or less than that.

Sleep health, obesity, and diabetes

Of particular interest to developers of wearable sleep tracking is the potential effect of sleep on fitness, metabolism, and obesity. A study from last year found that among subjects who were not obese at baseline, those who reported less than five hours of sleep per night had a 40 percent higher risk of becoming obese than those who reported seven to eight hours of sleep. In general, the study found an inverse relationship between sleep duration and weight gain. Another study found evidence that this might be a contributing factor to the "freshman 15" phenomenon of new college students putting on weight, as the college environment also lends itself to a decrease in sleep duration for many.

An academic book was even published in 2012 entitled "Sleep Loss and Obesity: Intersecting Epidemics". The book describes the relationship between sleep and obesity as multifaceted: lack of sleep might affect our ability to make good nutrition decisions and to know when to stop eating, but it may also more directly affect our ability to metabolize food. Obesity has also been tied to the disruption of circadian rhythms, which can happen to people like shift-workers, who get enough sleep but at an abnormal time.

An academic book was even published in 2012 entitled "Sleep Loss and Obesity: Intersecting Epidemics". The book describes the relationship between sleep and obesity as multifaceted: lack of sleep might affect our ability to make good nutrition decisions and to know when to stop eating, but it may also more directly affect our ability to metabolize food. Obesity has also been tied to the disruption of circadian rhythms, which can happen to people like shift-workers, who get enough sleep but at an abnormal time.

Studies like these show that sleep is the third piece in the trifecta with nutrition and activity for staying fit and maintaining a healthy weight. At a recent Boston event, Margaret McKenna from Runkeeper shared that most users of the Runkeeper Health Graph use it to incorporate either nutrition or sleep data into their run, and predicted that in the future, activity tracking products that want to stay competitive will focus on those three metrics.

Beyond obesity, sleep might also be linked to abnormal metabolism of blood glucose, making disrupted sleep a possible contributing factor to diabetes, independent of its links to obesity. A study published by the American Diabetes Association in June showed that shift workers with misaligned circadian rhythms had an increased risk for diabetes, for example.

Sleep health and cancer risk

Circadian rhythms affect the body on a cellular level, so they can even have an effect on the growth of cancer. Several epidemiological studies in the past decade have shown moderately increased risk for breast, prostate and colon cancer as well as non-Hodgkin's lymphoma in longtime night workers or shift workers. Another study showed that colorectal patients who slept better or moved less in their sleep had a better survival rate than poor sleepers.

II. The rise of sleep tracking with digital health tools

In recent years sleep tracking and coaching devices have become more widely available direct-to-consumer. At the same time big name providers and employee wellness companies are beginning to recognize the value of these tools and how they can support and complement activity and nutrition goals. As the number of tracking and monitoring devices increase there is an ever riper opportunity for analytics platforms to move in and unlock value from the health and fitness data people choose to capture. London-based Big Health with its recent $3.3 million round of funding to come to the US, may be one of the early contenders on that front.

As the number of tracking and monitoring devices increase there is an ever riper opportunity for analytics platforms to move in and unlock value from the health and fitness data people choose to capture. London-based Big Health with its recent $3.3 million round of funding to come to the US, may be one of the early contenders on that front.

The company’s first tool, Sleepio, aims to help users fix their sleeping issues. Users are asked to take a sleeping test and then upload sleeping data from a fitness device, Jawbone UP, Fitbit, or BodyMedia tracker, if they have one. From there, Sleepio creates a personalized program for the user to follow. “The Prof”, an online persona built into Sleepio, leads users through the program to help them learn cognitive behavioral techniques that will ideally improve their sleep schedules. The system also offers various tools including a daily schedule.

Sleepio’s weekly plan costs $24.99 per week, but users can cancel at any time. The company also offers a 12-week course that costs $149 and a one-year plan that costs $249. The company is collaborating with the University of Oxford to develop new sleep interventions.

Apple may be another company that helps bring sleep data insights to light through its recently announced HealthKit platform for developers includes a section for sleep tracking. While HealthKit is more of an aggregator than anything else, it also has partnerships with various EHR companies, which could integrate sleep tracking and other data into patient's records for review by providers.

The company also added a well known sleep expert and researcher to its medical team in recent months, signaling the importance of sleep tracking and coaching to the company's health and fitness plans. Apple hired Roy J.E.M. Raymann from Philips Research, where he led various sleep-related studies. Raymann was a senior scientist at Philips Research who founded the Philips Sleep Experience Laboratory, a non-clinical sleep research lab. He also led projects related to sleep and activity monitoring as part of Philips’ Consumer Lifestyle Sleep Research Program and Philips’ Brain, Body, and Behavior group.

The company also added a well known sleep expert and researcher to its medical team in recent months, signaling the importance of sleep tracking and coaching to the company's health and fitness plans. Apple hired Roy J.E.M. Raymann from Philips Research, where he led various sleep-related studies. Raymann was a senior scientist at Philips Research who founded the Philips Sleep Experience Laboratory, a non-clinical sleep research lab. He also led projects related to sleep and activity monitoring as part of Philips’ Consumer Lifestyle Sleep Research Program and Philips’ Brain, Body, and Behavior group.

Raymann will likely help Apple build sleep tracking features into its long-rumored iWatch device or he may just be helping the company to better work with existing sleep tracking companies and integrate their wares with HealthKit.

Sleep tracking devices are slowly making their way into employer-driven wellness programs too.

One example: last year the Mayo Clinic announced that it would offer up an program for its employer customers that leveraged mobile health devices, including those that helped users monitor their sleep.

The online platform will include a challenge platform for team-based and peer-to-peer competitions data as well as programs for weight management, physical activity, nutrition, resiliency, stress, sleep, tobacco use and preventive services. Employers will be able to tailor the offerings to their particular employee populations. Mayo Clinic Healthy Living will follow up with employees to track their progress.

III. A brief history of sleep tracking with digital health

Zeo Founded in 2004, Boston-based Zeo was the earliest entrant in the recent generation of sleep tracking companies. Zeo’s original offering was a sleep monitor that included a wireless-enabled, sensor-equipped headband that users wore at night and a bedside display alarm clock that captured the data transmitted from the headband. When Zeo was first conceived by a group of Brown University students 10 years ago, the idea was for an alarm clock that could wake you up at just the right moment in your sleep cycle, during the right sleep stage, so that you would awake feeling refreshed. Zeo’s alarm clock had this functionality built right in when it launched in 2009. Before that launch, however, the startup discovered in early product tests that users wanted a device that could do more than just wake them up better, they wanted to know how well they were sleeping, too. Zeo’s bedside display and subsequent reports showed users when they were in a certain sleep phase and then they awoke during the night. The company also created a composite score to help users to better understand how well they slept one night vs another — the score was called their ZQ.

Founded in 2004, Boston-based Zeo was the earliest entrant in the recent generation of sleep tracking companies. Zeo’s original offering was a sleep monitor that included a wireless-enabled, sensor-equipped headband that users wore at night and a bedside display alarm clock that captured the data transmitted from the headband. When Zeo was first conceived by a group of Brown University students 10 years ago, the idea was for an alarm clock that could wake you up at just the right moment in your sleep cycle, during the right sleep stage, so that you would awake feeling refreshed. Zeo’s alarm clock had this functionality built right in when it launched in 2009. Before that launch, however, the startup discovered in early product tests that users wanted a device that could do more than just wake them up better, they wanted to know how well they were sleeping, too. Zeo’s bedside display and subsequent reports showed users when they were in a certain sleep phase and then they awoke during the night. The company also created a composite score to help users to better understand how well they slept one night vs another — the score was called their ZQ.

Over the years Zeo added new suggestions to its sleep monitoring website, added mobile apps, transitioned into a sleep “coach” instead of a sleep monitor, and even offered a version that bypassed the bedside display alarm clock and transmitted right from the headband to the user’s smartphone via Bluetooth.

During its final year Zeo has had to deal with increasing competition from simpler activity tracking devices that suggested users wear them at night to get a basic idea of how well they slept based on how much they tossed and turned throughout the night. Activity tracker companies' more simplistic offerings may have been “good enough” to compete with Zeo’s more sophisticated sleep tracking capabilities.

Former talk show host Regis Philbin also famously tested out Zeo soon after it became commercially available, and after discovering how much trouble he was having sleeping at night, the data he gathered with his Zeo encouraged him to go visit his doctor. Turned out he had sleep apnea.

Zeo was always a consumer product and not meant for people who had sleep disorders. The company made early inroads with retail channels like Best Buy, back when Best Buy wasn’t selling anything related to health and wellness. Zeo made an effort to make clear that its device was not a medical device, but it also worked with medical researchers who were looking for a less expensive way to include sleep monitoring data in their research.

Zeo closed up shop in late 2012.

Nyx Devices, now Rest Devices

In 2008 MIT researchers formed Nyx Devices around a prototype for a sensor-laden shirt, called the Somnus Sleep Shirt, that the startup planned to launch commercially by 2012. Sensors in the shirt tracked the wearer's breathing throughout the night. It also used movement tracking and other data to determine for how long the wearer was in a REM period of sleep and how often they woke during the night.

Before long, Nyx pivoted, rebranded as Rest Devices, and began selling a baby monitor called Mimo that tracks a baby's respiration, skin temperature, body position, and activity level. The Bluetooth-enabled, sensor-equipped onesie also transmits the data via Bluetooth to a nearby base station device. Parents can then use the Mimo smartphone app to check in on their baby's biometrics as they sleep. Basic sleep analysis like time asleep and number of wake-ups and times are tracked too.

WakeMate Perfect Third was a consumer electronics startup and Y Combinator alum founded in December 2009 by Yale student Arun Gupta and Columbia student Greg Nemeth.

Perfect Third was a consumer electronics startup and Y Combinator alum founded in December 2009 by Yale student Arun Gupta and Columbia student Greg Nemeth.

WakeMate was a wearable device that used actigraphy to monitor when the user was in various sleep states. The data was sent to the user's mobile phone via Bluetooth to record the sleep data and to tell the user's mobile phone to wake them up during their lightest phase of sleep within a 20-minute window of their preselected alarm time. The company also offered tools on how to improve sleep times and quality.

WakeMate dealt with a number of delays, which is typical for hardware startups, but it did ship its product eventually. Uptake was not enough, however, and in mid-2012 Gupta wrote on the company's blog: "...as many of you have guessed, we have exhausted our capital and will no longer be making any more WakeMates. Currently our plan is to keep the service going while we work on open sourcing the technology. Hopefully this will ensure that you can continue to enjoy the product and its benefits even after the company no longer exists."

Lark

In 2010 Julia Hu founded Lark Technologies in Mountain View, California. The company offers smart alarm clocks, wristworn devices, and apps that track sleep patterns and quality, but originally focused on the value of a silent, vibrating alarm feature that promised not to wake up the wearer's sleeping bedmate. Other wristworn activity device makers have since gone on to add similar silent alarm features to their devices.

Lark Life

Lark Life

While it still sells sleep tracking devices, Lark eventually launched activity tracking wearables and standalone apps culminating in the 2013 launch of its wearable, Lark Life, which it positioned against other all-day activity trackers from Fitbit and Jawbone. The device promised to help users track and improve their nutrition, activity levels, and sleep.

In early 2014 Lark pivoted away from hardware to focus its energies on health tracking apps, beginning with a health app preloaded on Samsung's S5 smartphones. Those who bought the phone got a year of health tracking and conversational insights for free from Lark, but the service carries a $2.99 monthly fee after that. The app does not appear to include sleep tracking like its previous offerings, but many of those legacy devices still appear available for sale on the company's site.

Beddit

In mid-2013 Saratoga, California-based Beddit, founded in 2006, launched a crowdfunding campaign for a consumer-priced sleep tracking device after making similar sleep monitoring devices for professional and provider use. The company raised more than 500,000 in preorders for the device -- far beyond its $80,000 goal. The sensors are embedded on a strap that attaches to the user’s bed for both the professional and consumer systems. The professional line requires an additional device that sits at the user’s bedside and analyzes and then uploads the information to an online portal. In the consumer version, users check their sleep information from a companion app.

The sensors are embedded on a strap that attaches to the user’s bed for both the professional and consumer systems. The professional line requires an additional device that sits at the user’s bedside and analyzes and then uploads the information to an online portal. In the consumer version, users check their sleep information from a companion app.

The strap uses ballistocardiography (BCG), a method which uses motion sensing to detect individual heartbeats from cardiac contraction forces and breathing rhythm from chest wall movements. The strap measures bed time, awakenings and bed exits, sleep time, sleep latency (the time it takes to fall asleep), testing heart rate, sleep quality and breathing movements, which also analyzes if the user is snoring. From there the strap uses Bluetooth to connect with the companion app, which offers personalized coaching, a wellness diary, a history of sleep recordings and a social sharing option.

In mid-2014 Misfit Wearables, the company behind the Misfit Shine activity tracker, partnered with Helsinki-based Beddit to created a co-branded Beddit device sold by Misfit and integrated with its app.

While Beddit gives deeper analysis of sleep, it attaches to the mattress and is therefore impractical for people who travel a lot, the companies said. In that case, they can collect sleep data consistently through the Shine wherever they are.

Melon In June 2013 a crowdfunding campaign for Los Angeles-based Melon successfully raised hundreds of thousands of dollars for its EEG headband with built-in audio neurofeedback and Bluetooth connectivity. While Melon is primarily marketed as a tool to track focus and concentration, co-founder Arye Barnehama told MobiHealthNews at the time that sleep tracking could also be a future feature.

In June 2013 a crowdfunding campaign for Los Angeles-based Melon successfully raised hundreds of thousands of dollars for its EEG headband with built-in audio neurofeedback and Bluetooth connectivity. While Melon is primarily marketed as a tool to track focus and concentration, co-founder Arye Barnehama told MobiHealthNews at the time that sleep tracking could also be a future feature.

“Sleep is one example,” he said. “Sleep is often measured using EEG and other companies have tried that — like Zeo, which was not able to continue — so sleep is an area that developers are really excited to work on using the Melon platform.”

While Melon is currently taking preorders, it still has yet to commercially launch and its site does not advertise sleep tracking as one of the device's features at launch.

Withings While many consumer-facing, connected health companies have added sleep tracking features to activity tracking devices, so far only Withings has made the move to add a dedicated sleep monitoring system to its portfolio of devices.

While many consumer-facing, connected health companies have added sleep tracking features to activity tracking devices, so far only Withings has made the move to add a dedicated sleep monitoring system to its portfolio of devices.

In early 2014 Withings unveiled Aura, a sleep coaching system that takes a different form than most other sleep tracking and coaching offerings on the market today since it does not require the user to wear a device while they sleep. Instead, the system consists of a sensor placed in the user’s bed and a bedside device that serves as both lamp and alarm clock, which are controlled by a companion iOS app.

The bed sensor monitors body movements, breathing cycles and heart rate, while the bedside device senses ambient environmental factors like noise, light, and temperature. The bedside device also emits light and sound to help users fall asleep or wake up. The program is designed to help relax users as they fall asleep and help them wake up more easily in the morning by facilitating the release of the hormone melatonin into the body.

Withings  When San Francisco-based startup Hello was just getting started in late 2012, the team's original plan was to develop a new wearable device, but it scrapped those plans to focus -- at least initially -- on sleep tracking. This summer Hello raised $2.4 million in a crowdfunding campaigning for its sleep tracking, bedside device, Sense.

When San Francisco-based startup Hello was just getting started in late 2012, the team's original plan was to develop a new wearable device, but it scrapped those plans to focus -- at least initially -- on sleep tracking. This summer Hello raised $2.4 million in a crowdfunding campaigning for its sleep tracking, bedside device, Sense.

Soon after the crowdfunding campaign ended, Hello announced $10.5 million in backing from a group of angel investors that included former and current executives from Facebook, PayPal, and Xiaomi.

The Sense device is a small orb-shaped device that sits on a bedside table and tracks the noise, light, humidity, and temperature in the user’s bedroom. The device turns green when it senses the room is at an appropriate temperature, light level and noise level. Sense pings a user’s app if it finds their room is not a proper atmosphere for sleeping yet. The system also includes a small clip, called Sleep Pill, that attaches to the user’s pillow. After a night of sleep, the Sense app shows user’s sleeping patterns detected by the Pill clip as well as environmental data tracked by the bedside device.

Fitbit

In September 2012 Fitbit launched the Fitbit One, its third generation of wearable following its original device and the short-lived Fitbit Ultra. Fitbit One was the first device from the company that offered sleep-related features: hours of sleep, time woken, and a silent, vibrating alarm that users programmed via the Fitbit app.

In January 2013 the  When Jawbone announced the first version of its UP device in mid-2011, sleep tracking and a smart alarm that woke users up at an optimal time in their sleep cycle were among the device's main features.

When Jawbone announced the first version of its UP device in mid-2011, sleep tracking and a smart alarm that woke users up at an optimal time in their sleep cycle were among the device's main features.

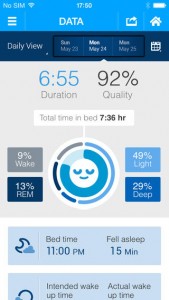

Unlike most other trackers with sleep tracking features at the time, the original Jawbone UP also estimated when and for long its wearer was in deep vs. light sleep throughout the night in addition to time awake and number of times woken up. It also determined an overall sleep quality index score for the night before, not unlike Zeo's Z score.

Of course, a few weeks after its launch, Jawbone famously offered refunds for its original fitness tracker after reports that the device had trouble synching with its companion app and even holding a charge. The second iteration of the UP, which launched in 2012, was more polished and had the major kinks worked out, but its sleep tracking features stayed relatively the same. One new feature was a power nap option, which promised to figure out when the wearer fell asleep and to wake them up 26.5 minutes later, while they were still in a light phase of sleep.

In the years to follow Jawbone quietly made sleep tracking a focus for its UP platform. It teamed up with big media outlets like The Wall Street Journal to create infographic-laden reports about the sleep habits of various countries and segments of the population.

Basis, now part of Intel

The latest update to the Basis Band looks to entice those interested in sleep monitoring and coaching. This sensor-laden wristworn device was the first to offer automatic sleep detection -- the user didn't have to tell the device that they were planning on going to sleep now by pressing or holding down a button.![]() To fine tune its sleep monitoring features, Basis recently teamed up with the Stress and Health Research Program, a joint venture between the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), the San Francisco Veterans Affairs Medical Center (SFVAMC), and the Northern California Institute of Research and Education (NCIRE), none of which were compensated by Basis for their role in the research.

To fine tune its sleep monitoring features, Basis recently teamed up with the Stress and Health Research Program, a joint venture between the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), the San Francisco Veterans Affairs Medical Center (SFVAMC), and the Northern California Institute of Research and Education (NCIRE), none of which were compensated by Basis for their role in the research.

Researchers compared sleep data from the Basis Band to data from polysomnography, the standard of care for clinical sleep assessment. It was a small study — only 12 participants were monitored for one or two nights each, for a total of 19 nights of sleep data. The Basis Band and polysomnograph each tracked the patients’ sleep states (REM sleep, deep sleep, and light sleep) as well as their sleep duration. For the former, there was a correlation of r = 0.92 between the Basis Band and the polysomnograph, a fairly high score (a perfect correlation would be 1.0).

Basis described the sleep tracking upgrade for its device as "the most detailed sleep analytics report available from a health and fitness tracker, which often will only break out a comparison of sleep vs. activity." Basis said one of the key differences was that its sleep report would no longer only "show sleep information night-by-night, but will now provide more context and insights for users by summarizing a full week of sleep.”

The report will include sleep duration, sleep score, number of tosses and turns, and number of interruptions. Weekly reports will help users compare weekend and weekday sleep and spot other trends in their sleep patterns, and Basis Band will also send sleep tips with the weekly emails.

iHealth

iHealth Labs, which offers a variety of connected health and fitness devices, also built in some basic sleep tracking features into its $59.99 activity tracking device, which commercially launched in 2013. The device tracks hours slept and times awoken. It also offers the now almost standard silent, vibrating alarm and a sleep efficiency score. Unlike other devices, the battery in the fitness tracker from iHealth does not require charging.

IntelliClinic

Late last year San Francisco-based IntelliClinic crowdfunded a brainwave-sensing smartphone-connected sleep mask, called NeuroOn. It’s a foam sleep-mask that contains several different sensors and a Bluetooth transmitter. It offers users several different ways to use the data it collects. The mask contains an electroencephalographic (EEG), or brain wave, sensor as well as sensors that measure the movement of the users’ eyes and facial muscles.

Late last year San Francisco-based IntelliClinic crowdfunded a brainwave-sensing smartphone-connected sleep mask, called NeuroOn. It’s a foam sleep-mask that contains several different sensors and a Bluetooth transmitter. It offers users several different ways to use the data it collects. The mask contains an electroencephalographic (EEG), or brain wave, sensor as well as sensors that measure the movement of the users’ eyes and facial muscles.

The data it collects on sleep patterns is meant to help users to adopt what’s called a polyphasic sleep schedule, a theory that suggests a person can sleep less overall by sleeping in carefully timed short spurts throughout the day. But the NeuroOn creators stress that the mask is also useful for standard sleeping. It can function as a “smart alarm,” waking the user immediately after a certain number of completed REM cycles with gradually brightening LED lights. The creators also claim that the device can help a user recover from jet lag or induce lucid dreaming.

Sony, Runtastic, Fitbug and more

With few exceptions, most every wristworn, accelerometer-equipped activity tracker on the market today offers some kind of basic sleep tracking. Sony's SmartBand, Runtastic's Orbit, and Fitbug's Orb among them. Virgin Pulse's Max also now offers a sleep management program that works its own device or data from others, like Fitbit's.

IV. Beyond wellness: Sleep monitoring for medical issues

Early in 2014 a report from Frost and Sullivan on the sleep diagnostic market suggested that the $97 million sleep device market was ripe for disruption by the consumer-facing upstarts described above.

According to the report, the combined US and European market for clinical and ambulatory sleep disorder diagnostic devices was worth $96.5 million in 2013 and is expected to hit $125.8 million in 2017. The report didn’t include consumer-facing sleep tracking devices, but rather multi-parameter polysomnogram systems that check EEG, ECG, movement, and breathing while sleeping. But even among clinical devices, the market is shifting toward home care.

“If you’re talking about the current market, the focus is shifting toward home testing,” Frost and Sullivan Healthcare Research Analyst Akanksha Joshi told MobiHealthNews. “If you are talking about the comparison of Europe and the US, Europe has been more accepting than US and most other countries of home testing. But in the US the usage is increasing. There’s a higher percentage of people accessing home sleep testing now, and it will grow to a higher number in the coming years.”

A number of sleep monitoring companies are developing devices and apps for home and clinical settings for people with sleep apnea and other medical conditions.

iMPAK Health -- Sleep Sensor In late 2011 Meridian Health, T-Mobile USA, and iMPak Health jointly announced the launch of the iMPak’s SleepTrack sleep monitor.

In late 2011 Meridian Health, T-Mobile USA, and iMPak Health jointly announced the launch of the iMPak’s SleepTrack sleep monitor.

The system has three components: a SleepTrak card (which is a credit card-sized wireless device that is worn on the upper arm), a free app offered through Nokia’s Ovi store, and T-Mobile’s Astound smartphone, which at the time was the only phone compatible with the SleepTrak device.

According to its developer, "the iMPak Sleep Assessment and Monitoring card enables patients to monitor their sleeping habits during the night -- in the comfort of their own home and get a better baseline of their actual sleep. The sleep assessment card is worn during the night and tracks overall activity levels associated with sleep and combines that knowledge with common daily symptoms into a core sleep assessment as well as a way to monitor the impact of changes to the sleep routine to improve sleep patterns. If a potential sleep disorder is clear, recommendations will be made to see a local physician specializing in sleep disorders -- at which time the data collected can be shared as baseline assessment results."

iMPak is a joint venture between New Jersey healthcare system Meridian Health and wireless technology firm Cypak that launched last year. iMPak aims to launch a number of reliable, low cost, easy to use solutions based on Near Field Communications (NFC), embedded sensors, and storage capabilities, for various health conditions.

Novasom In early 2012 NovaSom, which makes home tests for obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) unveiled an FDA-cleared OSA test kit that leverages Verizon Wireless’ cellular network to wirelessly collect and transfer sleep data up to a cloud-based platform for physician interpretation and diagnosis.

In early 2012 NovaSom, which makes home tests for obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) unveiled an FDA-cleared OSA test kit that leverages Verizon Wireless’ cellular network to wirelessly collect and transfer sleep data up to a cloud-based platform for physician interpretation and diagnosis.

Here’s how NovaSom described the test: “The AccuSom, NovaSom’s second-generation home sleep test, is a smartphone-sized portable Type III cardio-respiratory monitor. Its multichannel sensor system monitors the five parameters necessary for OSA diagnosis: respiration airflow, oxygen saturation, pulse rate, respiration effort and snoring.”

Physicians first prescribe the home sleep test, then patients receive the device in the mail. The device helps the user set it up through a series of voice prompts. The device collects data over the course of a couple of nights, which NovaSom claims is more effective than spending one night in a sleep clinic. About 12 million of the estimated 15 million people with undiagnosed OSA could benefit from using the device, according to the company at the time.

BAM Labs Later in 2012 BAM Labs, the maker of a smart bed system for hospitals and post-acute rehab facilities, offered up the first application that biometrically validated bed position changes through a secure, cloud-based monitoring platform. The new Position Change is an optional feature in the latest update to Bam Labs Health Monitoring app, which verifies whether a patient has changed positions in bed. This helps assure that patients are turned regularly to avoid pressure ulcers and alerts staff in case of a bed exit that can lead to a fall.

Later in 2012 BAM Labs, the maker of a smart bed system for hospitals and post-acute rehab facilities, offered up the first application that biometrically validated bed position changes through a secure, cloud-based monitoring platform. The new Position Change is an optional feature in the latest update to Bam Labs Health Monitoring app, which verifies whether a patient has changed positions in bed. This helps assure that patients are turned regularly to avoid pressure ulcers and alerts staff in case of a bed exit that can lead to a fall.

The app, which supports BAM’s Touch-free Life Care, or TLC, smart bed system, is available not only though the Web, but for Apple iOS mobile devices. Users can get immediate alerts on their iPhones and iPads in case of motion that could be the precursor to a fall. Bam reports that facilities using the app have seen a 43 percent reduction in falls out of bed and an hour of daily staff time saved per bed.

The TLC system is a mattress pad that detects patient motion as well as biometric signals such as heart rate and respiration. It transmits readings over the hospital or other healthcare facility’s network to Bam’s cloud for instant analysis, and data can be exported into electronic health records.

Night Shift

In mid-2014 Night Shift, a wearable that aims to both evaluate and treat problems with sleep apnea and snoring, launched a crowdfunding campaign that generated only about $17,000 of its $75,000 goal. While the crowdfunding campaign appeared to be ultimately unsuccessful, the company announced FDA clearance for the wearable once the campaign ended.

The device is worn on the back of the neck while the user sleeps, secured by a collar-like strap. Night Shift monitors sleep quality based on movement and snoring. But it also vibrates gently to encourage the user to sleep on his side rather than his back (many people only snore or snore more when on their back). Over time, the therapy trains the user to sleep on his back consistently. Backers at the $289 and up level opt into a 6-month usability and efficacy study that will help the company before officially going to market.

Appian Medical

Earlier this year Severna Park, Maryland-based mobile sleep apnea-focused company Appian Medical  According to a recent study published this summer, users of Philips Respironics’ SleepMapper app were 22 percent more adherent to continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy than non-users.

According to a recent study published this summer, users of Philips Respironics’ SleepMapper app were 22 percent more adherent to continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy than non-users.

SleepMapper is an app and website platform from Philips for patients with sleep apnea who are already using CPAP therapy, which involves a face mask that blows air into a patient’s upper airway while she sleeps. The system, which launched just over a year ago, allows patients to see the data generated by the machine and presents them with goals and feedback to increase adherence.

Fewer than half of those patients prescribed CPAP continue to use it after the first year, and an oft-cited study from 1993 found that the majority of CPAP users don’t use it as prescribed. Still, symptoms can improve if patients use CPAP for about 4.5 hours a night. SleepMapper aims to change that status quo with an established behavior change protocol called Motivational Enhancement Therapy.

To do the study, Philips analyzed 15,000 de-identified patient records from EncoreAnywhere, a database of use data collected from Philips Respironics CPAP machines.

Cambridge Temperature Concepts This summer UK-based Cambridge Temperature Concepts, which is best known for its DuoFertility system, raised $4.38 million to help it expand its product portfolio, potentially into diagnostic sleep monitoring.

This summer UK-based Cambridge Temperature Concepts, which is best known for its DuoFertility system, raised $4.38 million to help it expand its product portfolio, potentially into diagnostic sleep monitoring.

The company plans to use the funds to expand product sales in the US and develop the next iteration of the DuoFertility tracker, which will offer smartphone connectivity and the ability to measure more metrics. One such metric is likely to be sleep analysis, according to the company.

“In order to develop DuoFertility for ovulation and fertility advice, we had to address factors that affect fertility, such as sleep disturbance,” CEO Dr. Claire Hooper told MobiHealthNews. “We have CE marking for some aspects of sleep disturbance, and this is the area we will focus on next. As an outcomes-based company we see the potential to look other areas, for example working with groups such as pharma to address pain management, as it relates to sleep disturbance.”

Proteus Digital Health Another digital health company with peel-and-stick sensor technology that happens to track sleep disturbances, even though that isn't its core objective, is Proteus Digital Health. In a recent study that tested the effect of the company's medication adherence program and technology with a small group of patients.

Another digital health company with peel-and-stick sensor technology that happens to track sleep disturbances, even though that isn't its core objective, is Proteus Digital Health. In a recent study that tested the effect of the company's medication adherence program and technology with a small group of patients.

The main purpose of the study was to test the accuracy of Proteus’s digital health feedback system, which includes the ingestible sensor pill, a patch and a mobile app. Compared to tracking adherence by observation, the ingestible sensors tracked adherence with 94 percent accuracy.

The feedback system also tracked other statistics about the users including activity and sleep. Activity among the participants ranged from 847 to 15,930 steps per day and subjects slept between 3.2 and 15.2 hours per day. The system also tracked sleep disruption — the amount patients wake up during the night — a number that could be very useful in assessing the effectiveness of medication for a condition like schizophrenia, according to the researchers. Mean sleep disruption varied from 5 percent to 43 percent over the course of the study period.

Zansors

Earlier this year at the AARP event, a startup with designs on offering a stripped down peel-and-stick patch just for the purposes of sleep monitoring pitched its case from the event's podium.

Zansors believes the key to good sleep is breathing well. The company has developed a patch that users can wear on their neck that collects breathing sounds and movement. The company has not launched the product, but expects that it will cost $30 to $35 dollars. The product is Zansors’ answer to the gap in the sleep sensor market, where on one side, patients can pay $500 for a sensor test or pay $100 for a wearable that hasn’t proven its efficacy. Zansors aims to bring their product to market through B2B partnerships and then to sell it at retail clinics.

V. Where sleep tracking in digital health is headed next

The sleep market has taken off in a big way in recent years, and seems to be on a trajectory to get even bigger. Right now, unregulated consumer sleep trackers and FDA-cleared clinical home sleep tests are distinct groups, but the lines between provider and consumer sectors are already beginning to blur.

The Basis Science partnership (referenced above) with the Stress and Health Research Program, a joint venture between the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), the San Francisco Veterans Affairs Medical Center (SFVAMC), and the Northern California Institute of Research and Education (NCIRE), is one indication of the consumer-facing companies' move into the clinical realm. Conversely, Beddit, a longtime clinical sleep monitoring company, recently made a move to begin offering a direct-to-consumer version of its system.

Sleep health consultant Paul Valentine, senior managing director, KCP Advisory, thinks that many companies will always choose to stay consumer just to avoid running afoul of the FDA.

“I do think there’ll be this overlap between the consumer tracking area and the clinical testing,” he said. “There will be clear players who want to keep themselves separate, but there will be others that will start to overlap that. I also think there will be much better ways to communicate the data, to start to gather this information so there is more of a streamlined process for tackling a sleep problem. One of the biggest challenges we have is there’s such a disconnect between that consumer struggling with sleep, how do they become a patient.”

If sleep tracking manages to attain even the modest popularity fitness trackers are enjoying, that will spell an uptick in users who don’t already have symptoms of a sleep disorder. This could lead to more patients following in Regis Philbin's footsteps — discovering things like obstructive sleep apnea, which is currently a highly under-diagnosed condition.

There will certainly be tensions. Players in the consumer space have discovered that a segment of the population doesn’t want to wear anything while they sleep. So more and more consumer sleep tracker companies — Beddit, Withings Aura, Sense from Hello Health — are creating sensors that sit in the bed or at the bedside, or both.

For clinical applications, however, it will be a hard adjustment for consumers to start trusting trackers that don’t even have contact with the patient. Consumer trackers that want to dabble in the provider space will need to start investing in more substantial efficacy studies, to establish their competitiveness with the standard of care.

Meanwhile, home sleep health devices that want to compete on the consumer side need to make their devices smaller and smartphone connected. They'll also need to figure out how to translate data into insights for the user, not just to collect it and forward it to the physician. It’s a major shift in thinking for medical device companies, but one that could pay off as the consumer market for sleep health grows.

Just like in the activity tracker space, the market sentiment seems to be that tracking alone isn’t enough. Successful sleep devices in the future will deliver insights and solutions for sleeping more or sleeping better, yielding real positive change in the user’s life. There is likely market space for not just sleep trackers but sleep coaches, similarly to how run tracking apps have begun to evolve into digital fitness coaches.

And coaching software like that can go beyond just improving sleep health to target particular consumer issues: helping business travelers overcome the negative affects of jetlag, or even helping people to have more control over what they dream, a practice called lucid dreaming.

Valentine says the most exciting potential for more ubiquitous sleep tracking is a promise familiar to those in the mobile health space: personalized medicine. He wants to see consumer mobile devices moving not just to the assessment and diagnosis side of sleep health, but to the treatment side as well.

“I think we’re going to get to a point where the care process and the treatment process is much more patient-individualized,” he said. “There are many, many solutions for obstructive sleep apnea and for insomnia. What we need to do is figure out early on what treatment is right for that particular patient. And that’s an area where the consumer sleep tracking and the clinical testing can really help us."