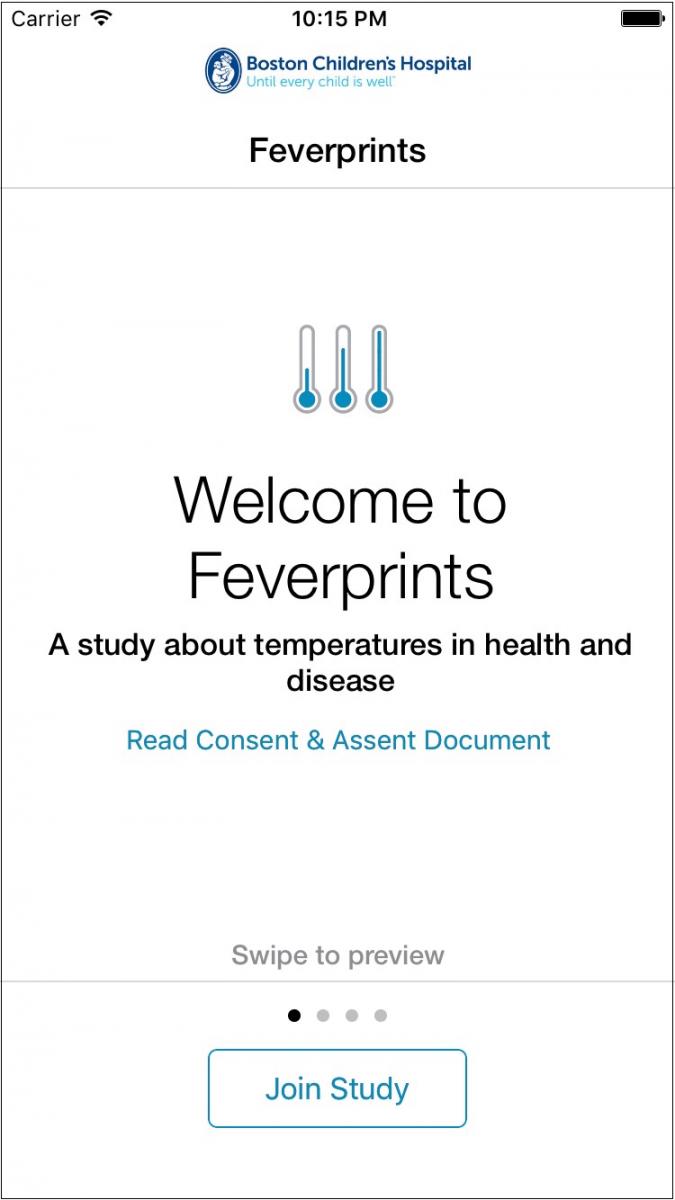

Boston Children's Hospital has launched its second Apple ResearchKit study, Feverprints. Rather than a focus on a particular disease, Feverprints aims to study fevers in general and challenge centuries-old assumptions about what's normal.

Boston Children's Hospital has launched its second Apple ResearchKit study, Feverprints. Rather than a focus on a particular disease, Feverprints aims to study fevers in general and challenge centuries-old assumptions about what's normal.

"For hundreds of years temperature has been associated with human disease, but we really don’t know that much about it," Jared Hawkins, director of informatics at Boston Children's Innovation Program and a research lead on the project, told MobiHealthNews. "Based on studies from hundreds of years ago, we have this notion that a normal temperature is 98.6 degrees Fahrenheit. That’s really not true. We know that there’s quite a bit of variation between different people and within an individual throughout the day."

People all around the United States will be able to download Feverprints and contribute information about their temperature (both when sick and when well), their medication use, any symptoms they might have, and demographic data. From the de-identified, aggregate data, Hawkins hopes to learn three things: what the range of "normal" temperature is, whether different diseases have identifiable temperature profiles, and whether fever-reducing medications actually improve recovery times or just treat symptoms.

Capitalizing on ResearchKit's built-in HealthKit integration, the study will allow patients to enter that temperature via a connected thermometer like Kinsa, Raiing, or Withings' newest device. But participants can also take their temperature with a non-connected digital thermometer or a mercury thermometer and then enter it manually.

Feverprints builds on similar research Boston Children's was conducting without the benefit of the ResearchKit framework. We reported last year on Thermia, a web platform that offered parents educational information in exchange for deidentified data about their child's fever.

"The purpose of Thermia was to be an educational tool for parents to better understand what to do when your child has a fever. We have done research from that on understanding the spread of disease on a population level," said Hawkins. "This was one tool that, in exchange for high-level aggregate information, would return back educational information. We've been interested in fevers for some time, but this is a bit of a deeper dive in terms of better understanding what 'normal' is, and why fever might be different between different diseases."

It's also Boston Children's second ResearchKit app. In October, the Boston Children's Computational Health Informatics Program (CHIP) released a ResearchKit app called C Tracker, that aims to study chronic hepatitis C, a liver disease. The app allows participants to track their health, medication use, and quality of life.

Boston Children's hopes to enroll a large number of patients in Feverprints in order to derive meaningful insights about body temperature.

"It’s so basic and it’s something that affects so many people," Hawkins said. "When you take your temperature or your child’s temperature there’s this comparison to this baseline and, at least in America, everyone’s head is at 98.6 degrees Fahrenheit. ... But I think when we better understand the population we’ll provide a service for people to help them understand that normal is a little different [for everyone] and can potentially change throughout the course of the day. Hopefully we’ll have success because we’re not asking a tremendous amount of time or information from people. It’s 'Turn on the phone, open the app, enter information for 60 seconds per day.'"