I don’t know about you, but when I read the FDASIA Health IT Report released by HHS on April 3, I found it to be largely quite predictable. Indeed I’ve been scanning the media coverage of the report and I haven’t seen anyone so far express shock or surprise at what was in the report. How is it that we all pretty much knew what would be in there? Quite simply the three agencies that wrote the report – FDA, ONC and FCC – studiously and carefully drew upon the prior work of a large number of organizations. They very specifically incorporated the work of the IOM Committee on Patient Safety in Health Information Technology, as well as the FDASIA working group that Congress had asked the agency to convene. Indeed the new center described in the report is actually already accounted for in the government’s fiscal 2015 budget.

I don’t know about you, but when I read the FDASIA Health IT Report released by HHS on April 3, I found it to be largely quite predictable. Indeed I’ve been scanning the media coverage of the report and I haven’t seen anyone so far express shock or surprise at what was in the report. How is it that we all pretty much knew what would be in there? Quite simply the three agencies that wrote the report – FDA, ONC and FCC – studiously and carefully drew upon the prior work of a large number of organizations. They very specifically incorporated the work of the IOM Committee on Patient Safety in Health Information Technology, as well as the FDASIA working group that Congress had asked the agency to convene. Indeed the new center described in the report is actually already accounted for in the government’s fiscal 2015 budget.

So if there’s very little new in the report, is that good or bad? Yes… A bit of both. On the plus side, it shows that these federal agencies are listening to an awful lot of very smart people. They are listening to medical and other experts enlisted by the IOM, they are listening to the public’s input as obtained through the FDASIA process and they’re listening to people on Capitol Hill. More on that later.

So why am I not completely happy? Well, I suppose I wanted more. Let’s take a deeper look.

Major Features of the HHS Strategy

If you really want to understand the report, you probably ought to read the 32 pages yourself. But I’ll give you the Reader’s Digest version here.

A three-tiered system

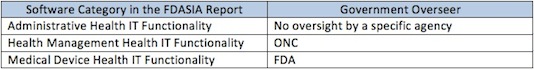

At a high level, the report says that health information technology can be stratified into three levels. Whoever originally thought of stratifying risk into three levels – high, medium and low --probably 1,000 years ago should have trademarked it because now everybody thinks about risk that way. For example, traditional medical devices are stratified into class I, II, and III based on risk. So in the new vocabulary of the report, we divide all HIT into three risk levels as follows:

Frankly I think someone in the government needs to go to naming school. Those titles do not exactly roll off the tongue. I guess they’re meant to be more descriptive than pithy. The drafters of the PROTECT Act came up with a pithier three-tiered system:

Of course, the problem with pithy is they are not very descriptive. Looking at those titles, do you have any idea how they differ?

The point is, it seems like everyone in this world agrees that software ought to be stratified by risk in three levels, high, medium and low. That, by itself, is not particularly insightful. Rather, the devil is in the detail in exactly how the government defines each of those three levels, and how to account for software systems that have more than one type of software. More on that in the section below regarding “The Insignificant.”

A largely voluntary program of quality management principles, cultivation of best practices, and private conformity assessments.

In the table above, I use the term “government overseer” deliberately because the role envisioned for ONC is not a regulatory one. In law, a regulatory agency is one that has investigative and enforcement powers, and the ability to prescribe binding requirements. The FDASIA report does not propose that role for ONC with regard to Health Management IT.

Instead the report spends page after page describing voluntary steps that health IT companies can participate in to improve the quality of their products. Frankly I can’t think of anything they left out. The thrust of it all is using a strictly voluntary approach to cajole health IT vendors into individually, and collectively, working to improve the quality of their products.

For example, they want individual health IT vendors to adopt quality management systems tailored to software development to try to ensure that the programs perform as intended. The report also suggests a more deliberate effort to identify, develop and adopt standards and best practices for the health IT industry. The report further recommends leveraging conformity assessment tools, and putting in place systems that will allow continuous learning and improvement. The report left out making apple pie, but I assume that was a typo.

When in doubt, create a commission

I was an avid high school debater. In those debates, the affirmative team would come in with a plan to accomplish something important, and the negative team would challenge it. Invariably, as kids learn from adults, the debaters would come in with a plan that calls for the creation of a blue ribbon panel to figure out how to solve everything, including world hunger. In a sense those plans were hard to attack because they didn’t specify what the blue ribbon panel would actually do, just that they would do great things.

The report recommends the creation of the Health IT Safety Center. The center would be created by ONC in collaboration with the other federal agencies and would serve as a “trusted convener of stakeholders and as a forum for the exchange of ideas and information focused on promoting health IT as an integral part of patient safety.” So I presume they are the ones who would actually bake the apple pie. Beyond that I’m really not sure what they would do. Based on the discussion that precedes the description of the center, I gather the goal would be to create a non-punitive environment to encourage the sharing of information such as adverse events. I’m picturing a bunch of health IT folks sitting around a campfire singing Kumbayah.

The Significant

All kidding aside, I think this report does accomplish some very important steps.

FDA will not expand its regulatory scope. Indeed the report says that several times. I think it’s very important for FDA to go on record as making that broad commitment, but I was also interested in specific limitations the agency agreed to:

On page 4, in the upper left-hand corner, FDA says that it does not plan to “focus its oversight on” the middle category, the health management health IT functionality. That’s a huge statement that’s very broad.

On page 6, FDA reiterates statements that it made in the September mobile medical app guidance that the agency does not plan to regulate cell phones and cell phone manufacturers simply because you can operate a mobile medical app on one.

On the bottom of page 23 in the lower right-hand corner, FDA also specifically says that if a piece of software that constitutes health management health IT happens to meet the statutory definition of a medical device but does not include the higher risk device functionality, the agency does not intend to require facility registration or product listing.

ONC will play the central role overseeing the middle category, the health management health IT functionality. Someone needs to take the lead in developing policy with regard to that group, and I think it’s a very wise idea for the three agencies to decide that ONC will carry that ball.

In the same vein, while ONC will exert leadership, they will not regulate that tier. For that category of software we should avoid regulation and instead use voluntary standards, certification and other private sector tools.

Adverse event reporting is important and should be improved, and can be improved by the creation of the Health IT Safety Center. I honestly don’t know what they will do, but I do support the effort to improve the collection of data about HIT safety. Virtually everyone in the FDASIA HIT advisory working group believed that there are gaps in our knowledge that could be addressed through better data collection and sharing.

The report recommends taking numerous steps to facilitate the interoperability of medical devices and health IT generally, used in systems. That’s an important aspect that’s been missing from some other HIT policy initiatives. The report expressly uses the word “functionality” to be clear that the regulatory divisions they propose have nothing to do with where a given program might reside. Obviously there’s a lot more than that to figuring out how to regulate systems, and especially the interoperability issues, but the report at least identifies these issues as needing attention.

I think all of those are good ideas, and frankly I think it shows that people in industry, on Capitol Hill, and in the agencies are largely in agreement. Indeed, it seems that all three sectors are saying about 90 percent the same things.

The bottom line is that HHS, and the three agencies, are proposing a very light touch to overseeing innovation in health IT, and that has to be good news for HIT developers.

The Insignificant

I hinted a few times so far that I’m not entirely satisfied by the report. Here’s why.

In December 2010, the mHealth Regulatory Coalition (which I co-founded and represent) issued a report entitled “A Call for Clarity: Open Questions on the Scope of FDA Regulation of mHealth.” In that 61 page report, we provided in detail numerous questions regarding the scope of FDA regulation that needed to be addressed so that companies wishing to develop mobile apps could do so with a clear understanding of whether FDA regulated those apps or not. Ever since then, now coming up on four years, we have been asking FDA such things as:

(1) Exactly when does a piece of hardware or software become an accessory to a parent medical device (and thus regulated with the medical device)?

(2) Where exactly is the dividing line between unregulated claims related to wellness and regulated claims related to disease?

(3) Exactly which types of clinical decision support software does FDA regulate and which do they not?

(4) How does FDA treat software modules that may be unregulated individually but are combined ultimately to form a regulated piece of software?

The mobile medical app guidance from September 2013 answered some of the frankly easier questions. But the more difficult questions listed above have remain unanswered for years now.

Quite honestly I was hoping that the report would take us at least partway down that road. It’s a report to Congress, so I understand that it must be at a high level, but at the same time I was expecting more – more detail and more answers. I am told that the public will have the opportunity to present these challenges at the public meeting on May 13-15, but that’s just the opportunity to present the questions. Presumably FDA is not going to answer them on the spot.

So what specifically would I have done differently if I were made King for the day (beyond ordering that I be paid a very high pension for the rest of my life)? Two things.

First, I was hoping the FDASIA report would have a more nuanced explanation for how a software developer could determine into which of the three buckets outlined in the report a given piece of software falls. Last summer I had the opportunity to serve on the working group that offered input to the three agencies in advance of this report, and indeed I co-chaired the regulations subgroup. As a part of that input, in the working group’s final presentation to the agencies, slide 20, the workgroup outlined about a dozen factors that could be used to discern high from low risk HIT. Those factors include things like the intended use of the software, the knowledge and experience level of the intended user, the seriousness of the disease being diagnosed or treated, the transparency with which the software operates and so forth. In the report from the agencies, I was really hoping to see the agencies’ assessment of those factors: do they agree with them, disagree, or are they unsure and need additional input? Do the recommended factors help put a given piece of software into the correct bucket? But I got none of that from the final FDASIA report: Just three simplistic buckets with no real words of wisdom to discern how a given piece of software might be placed in the correct bucket. I wanted more.

Second, I was hoping the FDASIA report would explain in more detail the future process for tackling the issues that remain. I was quite sure that the FDASIA report would not answer all questions. I don’t think anyone who’s watched Washington work expected that. The agencies did explain that they would be publishing Federal Register notices that would establish a 90 day comment period as well as the dates for a public workshop to discuss these issues. That’s pretty standard stuff for the government to collect additional input. But what happens after those 90 days? We really have very little idea, other than the FDA’s regulatory agenda written last fall did identify the development of several guidance documents of interest. So is that plan? Will we see those documents in fiscal year 2014? Presumably we would just see proposed documents – when can we expect the final ones? Again, I was simply looking for more substance, more meat with regard to the future plans of the agencies to tackle these issues.

So these important substantive questions remain about FDA’s oversight of software that constitutes a medical device, and while they remain companies must make investment decisions every day about whether to develop a high-value mobile app that may or may not be FDA regulated. Frankly that’s no way to do business.

The Desired Shape of the Ultimate Work Product

One of the more interesting aspects of the report was its discussion of clinical decision support software, or CDS. The report provided about a dozen examples of CDS that FDA would not regulate, and about a half-dozen examples of CDS that FDA would regulate. That was helpful, although quite honestly most of those examples were already known. But since I’m criticizing the report for not being specific enough, I thought I owed everyone an explanation for why even these examples fall short of answering my questions.

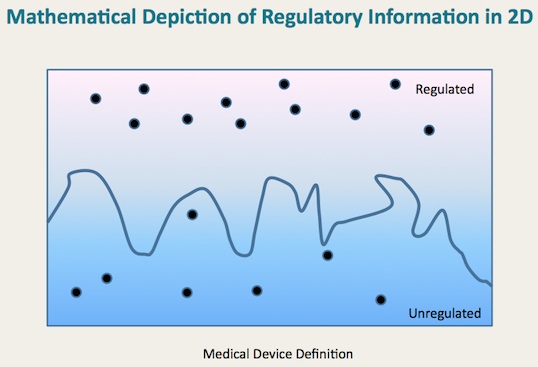

The examples that FDA provides are no substitute for understanding the rule that separates the regulated from the unregulated. I’m a math guy at heart, as you may know from prior posts. As geometry plainly teaches us, points are not lines. We need lines. We need to see the general rules that define the scope of FDA regulation. Unfortunately, the examples that FDA gives us have limited value because they are not even near the borderline. Instead, they are the outliers. So they don’t help us understand or discern the line that defines the boundaries of FDA jurisdiction.

Simply put, the points don’t define the jurisdictional line as illustrated in the following chart.

We need to define the line as well, and use the examples to illustrate points on either side.

Now let me hasten to add that I understand full well that the line is extremely difficult to draw, and the devil is very much in the details. In fact, we’re not talking about two-dimensional geometry but rather multivariate, and the true line that defines FDA jurisdiction is not even close to straight. It can’t be. Technology and medicine both are simply too complicated for the line that defines the risk associated with the intersection of those two disciplines to be simple and straight. If there were a straight and simple line, someone would’ve thought of it by now and suggested it. But no one has come up with that Holy Grail of health technology regulation.

So, speaking more practically, the final work product actually needs to be a detailed articulation of the lines (as complex as they may be), but also must include numerous example points. Those two techniques working together will be necessary to convey a full understanding such that technology developers can appreciate where their new technologies, not even on the drawing board right now, will fit in the future.

Ironically, during the very same week when the three agencies released their FDASIA HIT report to Congress, the International Medical Device Regulators Forum released a draft report on stratifying HIT based on risk. For those of you not familiar with the forum, it includes the regulatory agencies of the major developed, as well as many of the developing, countries. The goal of the forum is to encourage international harmonization with regard to the approach taken to regulating medical technology. Over the last year, the IMDRF has been working to develop an approach to regulating HIT stratifying it based on risk. After meeting the last week of March in San Francisco, on April 2 the forum posted to its website a draft report for comment that seeks to provide a risk-based framework for regulating what the IMDRF calls software as a medical device. I would urge you to take a look at it, because the author of that report is Bakul Patel of FDA. I think the IMDRF report is actually much more revealing and useful than the FDASIA report for understanding how FDA approaches software. But be advised, you might want to take an aspirin, because it’s very complicated. Indeed, while I have not yet filed comments on the recent IMDRF report, when I do I suspect much of what I will suggest is additional factors that need to be considered.

Where Do We Go From Here?

The FDASIA report makes some progress, but there is much work left to be done and in my opinion the process is going much too slowly. The kind of information investors and entrepreneurs are looking for is detailed and useful. High level political rhetoric, whether from the Administration or from Capitol Hill, does not allow industry to make the business decisions we need to make. We need to know, for example, does the FDA regulate the following:

An app that is built around a proprietary algorithm not found in any literature and not described in the labeling that is intended for returning soldiers who believe they might be suffering from PTSD. The app will guide them through an interactive process and ultimately offer a recommendation on whether the former soldier should seek the help of a psychiatrist.

Under existing law I have no idea whether FDA would regulate app. And I’m a professional. Making matters worse I could easily give you 100 other apps where the answer is nowhere to be found in existing FDA guidance.

Under the PROTECT Act, I do think the answer for this particular app is clearer. And the answer is no, it is not regulated by FDA. Is that the right answer? A poorly constructed app that uses dubious medicine could discourage a soldier suffering PTSD from seeking proper psychiatric help. Is that what you want? Complicating matters is the almost universal acceptance that we have a lot to learn about the risks the software may or may not create when used in healthcare. Do we want to lock ourselves into a particular approach through legislation, only to find next year that we misunderstood the risk drivers? Further, just about any legislative drafting will leave ambiguities and put us right back at the agency level asking for answers. New legislation only seems to help the attorneys hired to interpret them. (Wait a minute…)

So right now, our choices seem to be between:

(1) A status quo where those in the software development community cannot discern very clearly the scope of what FDA regulates in several key areas including CDS, the definition of an accessory, and the definition of a disease claim versus a wellness claim, or;

(2) Legislation that would clarify a few issues, confuse a few issues, lock us into a specific approach and ultimately produce outcomes in some cases that would not protect patients.

Please forgive me if I cannot get excited about either one.

So what would I do, other than complain? I think at this juncture we need to all coalesce around a path forward that holds FDA accountable for defining with adequate precision and detail the scope of software the agency regulates, using both lines and points, rules and examples. Until we get down to that level of granularity entrepreneurs and established companies alike will not be able to make the business decisions they need to deliver to the health-care system tools that will improve both the quality and efficiency of care.

The fact is we live in a complicated world and the technological whizzes developing mobile apps are coming up with so many different new and creative categories with so many new and challenging questions that no statutory language is going to resolve all of the issues for all time. Instead, we need the FDA to get going at a more nuanced level to sort the high from the low risk, and with a plan for updating that approach as we learn more. And we needed that years ago.

I for one hope the FDASIA process kicks into high gear.