This week, a Massachusetts law went into effect requiring health insurers to make realtime cost information publicly available, an unprecedented move. As WBUR reported recently, the initiative has already started to shine light on some galling price discrepancies for procedures like MRIs, surgeries, and lab tests (for instance, an MRI in Boston ranges from $614 to $1,800 with no discernible difference in the test).

This week, a Massachusetts law went into effect requiring health insurers to make realtime cost information publicly available, an unprecedented move. As WBUR reported recently, the initiative has already started to shine light on some galling price discrepancies for procedures like MRIs, surgeries, and lab tests (for instance, an MRI in Boston ranges from $614 to $1,800 with no discernible difference in the test).

This is a big step for healthcare cost transparency, but not the first and definitely not the last. One of the biggest IPO success stories in digital health, Castlight Health, offers price transparency tools to employers and insurers. In fact, both Tufts Health Plan and Harvard Pilgrim used Castlight to build their platforms to conform to the new law (Blue Cross Blue Shield used Vitals).

But even with more and more companies, legislators, and health plans dedicated to healthcare price transparency, it remains one of the biggest challenges to reforming the healthcare system, and one that often spurs disagreement about who's responsibility it is to make change.

Defining the problem: Why aren't healthcare costs transparent?

Healthcare is radically different from other industries for a number of reasons. The product or service being offered, medical care, costs a lot of money, yet there is an ethical obligation on the part of doctors to offer care when it's needed and work out payment later, and many people can't pay. This has led to an insurance system that takes on many of the costs of care -- which insurers are able to do because they charge healthy people (or their employers) for potential health services they might never need.

Insurers and self-insured employers negotiate with providers for the cost of certain services, because providers can afford to charge differently for employee population sizes and profiles. So there's no publicly posted menu for health services, and its very difficult for a consumer to comparison shop the way they're accustomed to in other industries.

But the Affordable Care Act is driving changes in this system for two main reasons -- the act is creating more and more people who have purchased their own insurance, without being part of a company's employee population, and the push towards accountable care and outcomes-based medicine is making providers take on more risk, causing them to be more conscious of the cost of particular procedures.

At the Economist Health Care Forum in September, Economist public-policy correspondent Roger McShane brought together payer, provider, and reform group voices to discuss the challenges of implementing cost transparency. One common thread was that cost transparency is more complicated than it looks because hospitals' billing structures for various services involved in care are so different, that just comparing two numbers might be apples and oranges.

Harold Miller, president and CEO of the Center for Healthcare Quality and Payment Reform, believes the idea of cost transparency is tied up with the idea of payment reform for this very reason.

"What’s the price that’s transparent?" he asked. "If it’s individual small services, [consumers] end up thinking the price of that is lower, but they end up getting more of those services, and the total cost is really what should matter to them. And today it’s very difficult for people to find what the total cost is going to be. They pay for the hospitalization, they pay separately for the business end, they pay for readmission, they may pay for post-op care, and all those things they pay separately. Moreover, and I think more problematically, if something bad happens to the patient and that has to be taken care of, they pay for that too. ... Just like every other industry, in healthcare there has to be a warranty of care, so whenever healthcare providers are providing care and there is a problem that arises, they should address that problem at no charge to the patient. And if you have that total package then it’s a lot easier to evaluate and to compare providers with each other."

Stephen Ondra, a senior vice president and chief medical officer at Health Care Service Corporation, an insurer, agreed that price transparency without payment reform wouldn't address the real cost problems in healthcare. With nothing but cost transparency, it might not be obvious that a somewhat expensive preventative measure could prevent a much more expensive surgery down the road.

"Today one of the reasons we’re spending so much is it is all about people who’ve delayed care and ended up with much more expensive conditions than they would have otherwise, and I think what you don’t want to do is say 'OK, you’ve avoided colonoscopies and now you’ve got metastatic colon cancer, where is the cheapest place to go and get your care?'" he said. "What you want to say is, so how can we get you better care up front so you don’t have to face those costs?"

At a recent Health 2.0 event, however, Healthsparq VP of Product Tamara Khan shared how her digital health platform can approach these problems with data analysis and user experience.

"At HealthSparq, we run a rich set of statistical analysis on the claims data to mark out the arc of care for a treatment," she said. "A treatment doesn't begin and end when you walk into the office and walk out. At the end of the day, there are a number of costs that pop in [during] the evaluation phase and afterwards in the followup. So even though I might find a place where a surgery only costs $2,000, in reality the scans, the doctor visits that happen in advance have a dramatic impact on price."

She used the example of a neighbor with a torn ACL, who didn't realize that his surgery, which was preceded by a thousand-dollar MRI, could just as easily have been facilitated with a $70 X-Ray, something their forthcoming product could have demonstrated.

Cost transparency and quality transparency

That leads to one of the other consensus points among the Economist panel: Cost transparency in a vacuum is unhelpful and misleading -- customers also want transparency about the quality of their care.

Leah Binder is the president and CEO of the Leapfrog group, a national non-profit focused on creating public quality measures for hospitals including patient safety report cards.

"Is there anyone in this room who would ever say ‘I’m going to choose a hospital for my sick child based solely on cost?’" she said. "We make some tough decisions in our lives and we always consider price, but we also consider quality."

Ondra expressed a similar sentiment, saying that "cost is necessary but not sufficient. This is healthcare. This isn’t a commodity, this is our lives. So we are very committed to value transparency and that brings in quality and cost."

Miller went further, arguing that the secrecy surrounding healthcare costs arises from an obsession with cost that doesn't take quality of care into account.

"That arises because we’re obsessed with the price, but we’re not obsessed with anything else," he said. "Everybody focuses on what’s the discount from the price, and everybody wants to get the best discount and oh, by the way, it’s got to be secretive. And what we have today is random price discrimination. So one person my end up paying five times as much as somebody else does, simply based on what kind of health insurance they have. That’s crazy. You don’t go to the grocery store and they say ‘Tell me who you work for and I’ll tell you how much the bread costs.' They say 'Here’s the price.’ And it should be the same everywhere else. But right now the focus is based solely on price and not on overall quality outcomes."

But Binder feels that opening up price transparency can and should be a gateway to better transparency about other parts of the healthcare system.

"While we’re focused on quality and safety [at Leapfrog], quality and safety are the second question always asked, after price," she said. "None of us walk into a car dealership and says "I have $20,000, give me a car, period. They say 'What do you have for around $20,000?' That is my preferred price, but my second question is ‘what do I get for that?’ ‘what are the features, benefits?’ That is exactly what we see happening, and that’s why we think, from Leapfrog’s perspective, that this move of providing price transparency to the American public might be the gateway to a far more informed consumer."

But quality is a more abstract notion than cost, and comparing it is a sensitive business. After all, medical boards and licensing laws should theoretically mean that there are no bad doctors, at least not bad enough to be untrustworthy with patients' lives. Doctors worry about what showing up on the bottom of a quality report -- based on anything from subjective patient reviews, to aggregated patient outcomes, to error percentages -- could mean for their practice and reputation.

Dave Mason, senior vice president at RelayHealth said that fear is one of the roadblocks making it hard to get uniform quality comparison measures.

"You can bring payers and providers together, but we want to make it so the information is standard and people can make meaningful decisions. Take quality, make it uniform, and publish it," he said. "We’ll work through it, but the problem is no one wants to be on the bottom of the list. So we have to finally find a way to get enough momentum and push it over, because after we do that we’ll then raise the bar."

Who's responsibility is transparency?

The other dominate conversation at the Economist forum was how employers, insurers, and providers can work together to create transparency. Ondra, the payer on the panel talked about how it has to be a group effort from various stakeholders.

"I believe we’re an important part of the solution. We all have to work together. All stakeholders in the healthcare field -- the consumer, the payer, the provider, the suppliers of pharmaceuticals and devices -- we’re all in this together and we’re going to be stronger together. In the payment reform space... unless you’re aligned with someone’s incentives you don’t get a lot of traction."

But panelists agreed that it wasn't as simple as that. Different stakeholders have a hard time trusting one another, and that's one of the factors that's led to the current situation in payment opacity.

"At Relay, we work with probably 60 percent of all US hospitals, and we run these site solutions together with 90 percent of US payers," Mason said. "So we’re sort of sitting in the middle of two large entities that, quite candidly, just don’t trust one another. And their work is exception-based, and everything is ‘why won’t it work’ versus ‘how do you make it work?’"

Miller agreed, and also spoke about the difficulty of asking stakeholders to take on new risks.

"The problem is that there’s a lack of trust out there," he said. "And if you want to move from the current system to a different system, then you have to have the payers and the providers trust each other. And if everybody thinks everybody else is a villain and 'They’ve been trying to screw me for years and now I’m going to get them back through this process', no one is going to feel comfortable going through something that is. We can get there, but it’s a scary thing and that transition can be rocky, and you want to feel like you’re getting there in a way that you’re not going to lose your shirt."

But Mason thinks that lack of trust is starting to erode in the face of consumer-driven healthcare stemming from the Affordable Care Act. As consumers have more of a choice than ever about which insurer to sign up with, insurers and providers will come together to create that marketplace, and to vie for a position as the top choice within it.

"So the beauty is we’re starting to see that change," he said. "We’re really seeing that the entire industry is going through a huge transformation. We talked about value-based reimbursement, we talked about changing the way we pay, but really what’s happening is consumers are getting involved. And for the first time in my career, the consumer, or the individual patient, whichever term you want to use, is finally being engaged in healthcare. We now have the ability to make a decision. Not the employer. Not the payer, not the hospital, but us."

There's inherent conflict in the relationship, though. Binder suggested that payors will need to be more aggressive to get providers to drive down unnecessary costs that will become apparent because of cost transparency (she was speaking specifically about the costs of preventable medical errors.)

"I think they need to orchestrate a market push," she said. "And pushes sometimes are tough, and they’re not going to be Kumbayah conversations. They’re going to be tough conversations about saying 'I’ve had it with the problems that my patients are encountering and paying for those problems, it’s time for me to come into the market and get better service for my employees.' And that simple market conversation that we see in other industries doesn’t happen as much in healthcare and we need it to."

Miller, on the other hand, felt it was the employer's responsibility to make changes in order to facilitate payment reform.

"The problem with employers is that employers aren’t actually changing health plans today," he said. "They’re sticking with the same health plan and saying it’s the provider’s problem, which is the villain problem. They need to be saying 'Let’s come up with a different way to pay. We employers will pay differently if you’ll accept a different way to pay, which will actually be better.'"

Cost transparency and quality transparency, payment reform, and consumer choice in healthcare are all trends that are underway, all phenomena that are already here. But as consumers begin to adopt them and hospitals and payers start to feel the pressure of the free market in healthcare, the system is poised to change dramatically. It will take payers and providers working together, for the benefit of consumers and patients, to weather that change.

While there are many companies working on price transparency problems in healthcare, MobiHealthNews has rounded up 11 such companies. These include companies that offer tools to compare prices of healthcare services and medications:

Castlight is arguably the biggest price transparency company in the space. It went public at the beginning of the year and has since signed 29 new employer customers, including Google, Spring, Kellogg, and the state of Kansas.

Castlight Health offers employees a personalized platform, online and on iOS or Android, to compare prices of healthcare services and keep track of healthcare spending so that their employers can reduce that spending over time. The company also integrates prescription drug information into the platform so that they can also track medication cost. It also recently added a dentist pricing offering.

Earlier this year, Castlight announced that it had partnered with telehealth service provider Teladoc. The deal made it easier for employees whose employers are customers of both companies by integrating Teladoc’s virtual visits services into Castlight’s platform. On the company's second quarter conference call, Castlight said it has found its users are twice as likely to use telehealth services than non-Castlight users.

Medlio has launched an app that will act as a virtual insurance card and enables users to see their health insurance benefits information, including as co-pays and deductible balances; a map to find doctors, hospitals and pharmacies near the user’s location; an appointment check-in service on the app; and another portal to pay for appointments. The company's cost transparency tool, called Common Cents, has not launched yet.

The company also hopes to one day replace the merchant services that are currently in place at doctor’s offices through a partnership with companies like Paypal or Square and monetize Medlio through transactional fees. While these merchant services probably charge doctors three to five percent in transaction costs, Brooks estimates if Medlio had a partner, he could charge three percent, if not less.

Unlike Medlio, Healthcare Blue Book is already offering users a cost transparency tool for visits, procedures, and medications. The company's services are available online and via iOS and Android apps. Healthcare Blue Book offers a free version of its search tool, which is available for anyone to use by visiting the company’s website and entering in a zip code. They also have a premium version, which is available to consumers only via their health plan or employer.

Healthcare Blue Book uses an algorithm to not only offer various prices for services, but also provides a "fair price" for that service. Earlier this month, the company raised $7 million from a single, strategic investor, The Martin Companies, which will be used for scale and growth.

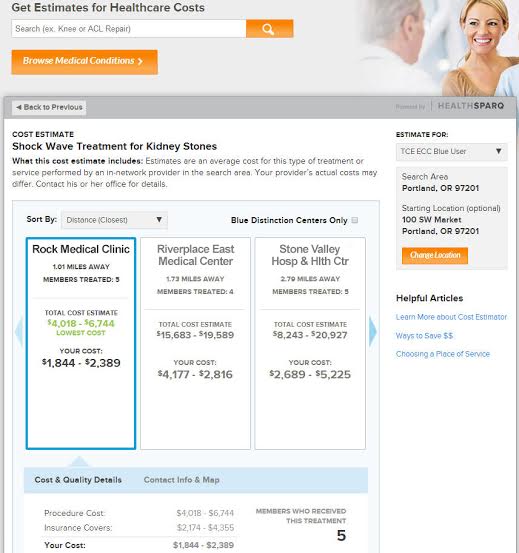

HealthSparq is a subsidiary of health system Cambia Health. The company offers users an online platform to shop for healthcare services. The company partners with small, regional health plans to offer the plan’s members comparison shopping on an online platform. It uses the plan’s existing data to show users various costs and times involved with different procedures, and it also shows the price and quality of different providers. Users who want to pay out-of-pocket can use a calculator that HealthSparq also makes available.

At the begnning of 2014, the company acquired ClarusHealth Solutions, an online provider search tool, which brought HealthSparq's total number of health plans from 20 to 60, a total of 60 million consumer users.

Although the site is web-only, it uses responsive design to make the tools accessible on mobile devices.

UnitedHealthcare, an insurer, launched a cost transparency tool for their members along with an appointment booking system, which the company announced at CES this year.

The system, which is called myEasyBook, is geared towards users of high-deductible healthcare plans, like those linked to health savings accounts or health reimbursement accounts. These users can compare the costs of different available providers in their network.

The software calculates the out-of-pocket price to the user based on his or her insurance information and searches multiple providers by condition.

In July, UnitedHealthcare opened up one of its mobile health apps, called Health4Me to the general public, two years after the company first launched the app for its members. The Health4Me app allows users to access their health information and their families’ health information in one place. Users can also find healthcare facilities in their area and compare prices for 520 medical services across 290 episodes of care so they can better estimate their healthcare expenses.

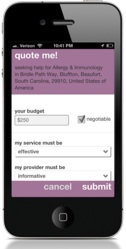

PokitDok, founded in 2011, launched its iOS app in December 2012. The app, which is also available as an online service, allows users to find healthcare providers in their area and do a price comparison of different price quotes. If a provider doesn’t have prices listed, users can fill out a form describing their medical needs and payment options — cash, insurance, or healthcare savings account — and get a quote from the provider.

The company makes a point of including as many types of care providers as they can, including acupuncturists and homeopathic practitioners. Users can also rate their experiences with providers publicly on the app.

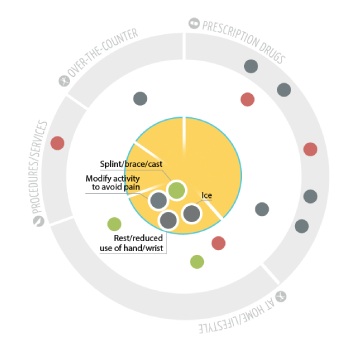

WiserTogether’s offering aims to help personalize the decision-making process for patients who want to choose which healthcare treatments they should receive. The platform helps guide and inform the patient on treatment options based on 22 factors, including clinical evidence, personal and popular preferences, cost, and coverage.

For example, if a patient has carpel tunnel syndrome, they have 18 different treatment options, like taking brand-name OTC drugs, changing hand positions for repetitive tasks, using compression and ACE bandages, elevating the injured wrist or hand above the heart, and taking generic/store brand OTC drugs. WiserTogether helps patients better understand how each of these options differs from the next.

The service covers 250 health conditions, including heart disease, diabetes, musculoskeletal conditions, mental health, and pregnancy, and offers up 4,000 treatments.

Rock Health alum HealthinReach is a free online platform that aims to help patients find low prices from dentists and doctors and book appointments online. The company said it offers descriptions and prices for nearly 50,000 specific procedures and has so far seen 3 million users on the website.

GoodRx is a bit different from the others on this list, because this company focuses on price transparency for medications instead of medical services. The company launched their transparency tool in 2012 and partnered with Aetna in June of 2012 to provide data to developers looking to build apps with APIs managed by Aetna.

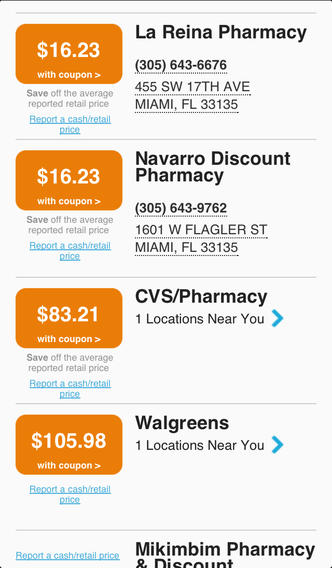

To use the app, people enter in the name of the prescription they plan to purchase along with their zip code. The app then shows a list and map of prices for the brand name and generic versions of the drug the user is seeking — both from local brick-and-mortar pharmacies as well as mail order ones. The app also offers refill reminders and price alerts.

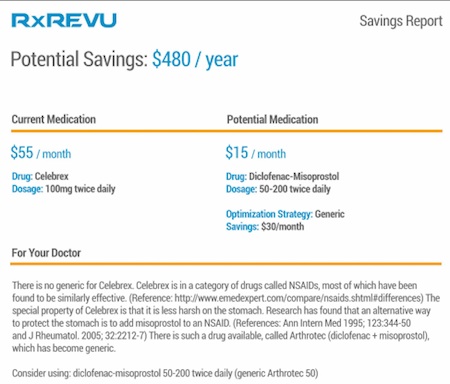

RxRevu offers a medication transparency tool. The service provides data to various healthcare groups on how to save money when buying medications. The company has catalogued thousands of generic drugs. RxRevu has seen interest in using its product from different healthcare sectors that deal with medication pricing including payors, providers, and healthcare app developers that focus on digital health tools and medication adherence apps.

This app helps patients compare the prices for drugs available at their local pharmacy while at the doctor's office or on their way to get their prescription so they can make the right decisions about which medications to purchase. The app aggregates data from several pharmacies including CVS and Walgreens.