When Kenneth Stack's son was diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes just before his fifth birthday, the doctor told Stack he was just a few years too early for a major medical breakthrough.

When Kenneth Stack's son was diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes just before his fifth birthday, the doctor told Stack he was just a few years too early for a major medical breakthrough.

"I remember, trying to make sense of all of this, the doctor saying 'In three years, we’ll have perfected the artificial pancreas and you won’t have to worry about this'," Stack recalled at a panel discussion at the HIMSS Connected Health Conference just outside of Washington DC. "That was 2003. For nine years, nothing changed."

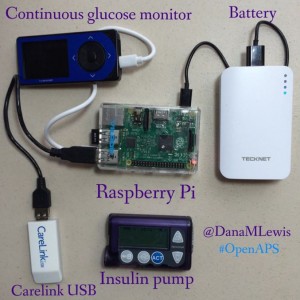

Nowadays, continuous glucose monitors are common and so are insulin pumps that can automatically deliver insulin to people with diabetes. But the artificial pancreas -- a software and hardware platform that would combine the two and regulate patients' insulin seamlessly and automatically -- has proven more elusive. Not because it can't be built, but because so far it hasn't been built in a scalable, reliable way.

This hasn't stopped an ever-growing cohort of hacker patients, united on social networks under hashtags like #WeAreNotWaiting, from building their own solutions. A few of those patients who presented at HIMSS CHC included Stack; Nightscout developer Ben West; Dana Lewis, who built her own "DIY pancreas"; and Galileo Analytics co-founder Anna McCollister-Slip. Courtney Lias, director of the Division of Chemistry and Toxicology Devices at FDA, weighed in on behalf of the agency.

What's both amazing and frustrating about these DIY solutions is that they're so personalized. Lias commended a system Lewis built that allows her to monitor her blood glucose while she sleeps and automatically alert friends if it drops too low and she fails to wake up and correct it.

"The risk in that scenario isn’t high," Lias acknowledged. "But the closer you get to creating an artificial pancreas, you are certainly introducing more risk to the patients using them. Inadvertently giving too much or not enough insulin can cause harm." Patients like the presenters at the session "understand what they’re doing, what they’re trying to do and the potential risks they might be taking it on. If someone’s online and telling other people how to do it, that’s different. That person didn’t design that system, they don’t understand the limitations. Potentially aspects might not be appropriate for other people."

Patient hackers recognize that they need to strike that balance between making their methods available to empower other patients, and not putting patients at risk by giving them complex tools they aren't ready to use.

"Publishing 100 percent of our code is not the right thing to do," Lewis said. "Because to operate the system, you need to know the 20 ways it’s going to break in the future. So the FDA and I are 100 percent aligned on that."

Eventually, the industry catches up, at least to some degree. For instance, the FDA helped Dexcom expedite the release of its Dexcom Share platform, partially in response to the NightScout project. But West and Lewis said there will always be another advance patients are ready for before it's official.

"The community is very excited," West said. "[Dexcom Share has] enabled a lot of people to get that much more control. But frankly, we want more. That’s the trick, every time you launch a new feature they’re going to write back and say 'Why doesn’t it do this thing also?'"

And what's more, there are some things that might never come to the official FDA-cleared apps.

"Our features tell you what’s going on inside the device, whereas the vendor may not want you to know what’s going on inside the device," West added.

To that point, West was recently a plaintiff, along with high-profile e-patient Hugo Campos, in a copyright case that could have broad-reaching affects on patients getting legal access to their own medical data. With the help of Harvard's Cyberlaw Clinic, West, Campos, and two other patient researchers got a three-year exception to the copyright protections that would have kept them from accessing data from their medical devices, including West's CGM and Campos's implantable cardioverter-defibrillator.

West told MobiHealthNews in a post-panel interview that the victory was a win, but there's still a long way to go. Patients don't just want temporary legal access to their health data, they want to own it.

Meanwhile, the various patient hackers of the #WeAreNotWaiting movement are looking to keep balancing on that tightrope of empowerment and safety.

"Today it’s a huge effort to put the system together," said Stack, who uses his own Perceptus system as well as others' innovations to manage his son's diabetes. "That's a nice barrier to entry because we don’t want to hurt anybody, but for us the question is how do we scale this in a safe and responsible way?"