(Several friends commented on this draft, and I would like to thank them.)

Warning, this article contains explicit and sometimes graphic depictions of possible FDA regulation.

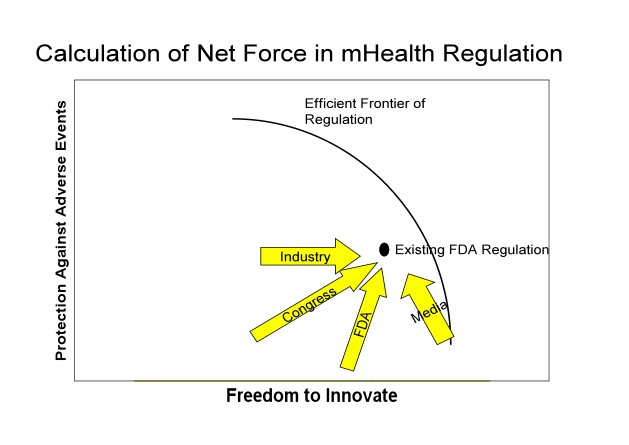

If you've been reading the prior articles in the series, you know I've been leading up to this last article in which I offer some predictions as to where FDA regulation will end up with regard to mHealth technology. Rather than just give you my predictions, however, I'm going to show you how I arrive at them. In this article, as the basis for my prediction, I use the political science equivalent of Newton's second law of motion: the acceleration of an object is directly proportional to, and in a direction determined by, the net force acting on it. I also throw in a little portfolio theory, just to spice it up.

Borrowing from Newton’s law, I identify the vector forces that represent each of the primary social and political constituents affecting FDA regulation. As I identify them, I estimate both the magnitude and the direction of the force. Actually it's easier to communicate this in a graph.

Function

If that graph doesn't help you, just forget it, and go to the next section. But if you'd like to know more about how I designed it, read on. I'm a visual person, so I always try to draw myself a picture.

Innovation and protecting against adverse events can be inversely related, at least in certain instances. Requiring medical devices to go through FDA approval, for example, restricts the freedom to innovate in some measure (you can't just put a beta version out on the market and see how it does), while presumably reducing the risk of adverse events if FDA reviewers catch problems. On the other hand, there are places where regulation may actually enhance innovation by providing a framework to ensure the vigor of the analysis. Some argue that design controls lead to better, and in a sense more innovative, products. But for purposes of this analysis, let's assume that there's a trade-off between innovation and protecting against adverse events.

So basically Congress and FDA pick where on this graph they want to be in terms of that trade-off between permitting innovation and protecting against adverse events. But what determines their choices? Ideally they would like maximum innovation and maximum protection against adverse events. So they want to be at the far, upper right hand corner.

Unfortunately, it's not that easy. Their choices are constrained by reality. Perhaps limited by our collective creativity but also by the fundamental conflict between a business process that encourages creativity and innovation, on the one hand, and a business process that drives toward zero risk on the other, trade-offs are necessary. We haven't invented the perfect regulation that allows both maximums.

On the right-hand side of the graph, I depict those constraints, calling it the efficient frontier of regulation. I got kind of carried away, making an obscure reference to an economic theory developed by Nobel prize winner Harry Markowitz. In his famous graph, he shows the trade-off between risk and return from owning various bundles of stocks. His efficient frontier was a curved line representing the best trade-offs you could make in terms of risk and return. That line represented choices in the perfect market.

By

By