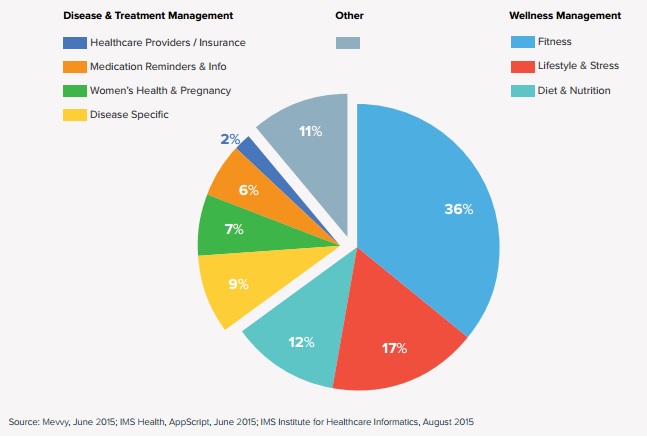

There are more than twice as many health apps as there were in 2013, but whether those apps are better tools for doctors and patients is a mixed bag: while apps today are more likely than two years ago to connect to another device or wearable and more likely to connect to social media, they are no more likely to connect to provider systems or to have more than one function, according to a new report from IMS Health.

IMS found 165,000 health apps across the iOS and Android app stores. They subjected a subset of 26,000 apps for a more in-depth analysis.

"App connectivity has been a major focus for developers," Murray Aitken, Executive Director of the IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics, said in a conference call with reporters. "We now see that one in 10 apps has the ability to connect to a device or sensor and that therefore opens up the ability to bather biofeedback and physiological functional data from patients, which clearly goes a long way toward extending both the accuracy and convenience of data collection. We also note that during the past two years the percentage of mHealth apps with the ability to connect to social networks has gone from 26 percent to 34 percent. And again, we think that that underscores the importance of social networking in consumer engagement."

However, the percentage of apps that actually connect to a provider's IT systems, like an EHR or clinical decision support software, was just 2 percent. And the physicians and hospital IT personnel IMS spoke to for the report also named that connectivity as a top challenge for integrating mobile apps with their care.

Part of the problem is that, although there are more systems in place for providers to recommend or prescribe apps to their patients than there were, IMS still believes most patients are either choosing the most popular app -- which might not be the best-suited app clinically. The study found that 90 percent of downloads encompassed just 12 percent of apps, and that 40 percent of apps have less than 5,000 downloads.

"We are coming from the perspective of the use of apps for real healthcare issues, whether that be diet and exercise and fitness or whether it be COPD monitoring or BP or diabetes monitoring and so on," Aitken said. "I think in that context, the issue is, how does a patient or a healthcare professional narrow down the choices to something manageable in terms of one that would be appropriate for them? The most popular one would not necessarily be the best for a particular patient in a particular circumstance. This is also why we do things where the role of healthcare professionals can actually be rather important in helping the patient see their way to find the sort of app that will help the most."

Of course, IMS does have a vested interest in believing the number of choices in health apps to be a problem -- the company's AppScript platform is designed to address this situation. Aitken also shared some data from AppScript, showing a 10 percent higher average utilization rate after 30 days for apps recommended by a physician and a 30 percent higher retention rate for fitness apps recommended by a physician.

Aitken said IMS also analyzed medical literature and ClinicalTrials.gov to assess the state of mobile health efficacy data as compared to 2013. Their conclusion was that there is a lot more data than than their once was, but still not enough to robustly support the use of mobile health.