Back in April, Borderlands 3 – a big budget, role-playing first-person shooter videogame that sold over 8 million copies within six months of its release – received a free update that introduced a new mini-game to its players.

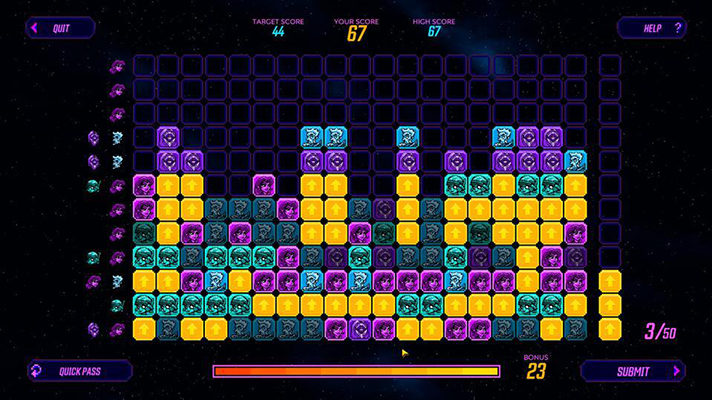

Taking the form of a retro-style arcade cabinet in the home base's medical bay, "Borderlands Science" has players shifting colored blocks between rows and columns to solve puzzles. Their successes are rewarded with in-game currency, which players can then use to better combat the aliens, mercenaries, machines and space cultists of the main game.

But Borderlands Science has a bit more than high-score calculations going on under the hood. The colored blocks and puzzles that it's serving players each represent nucleotides and fragments of microbial 16S ribosomal RNA gene sequences, all of which were collected from human stool samples contributed to and sequenced by an open research platform called the American Gut Project.

Rather, Borderlands Science's true goal is to help artificial intelligence iron out errors when organizing and analyzing those sequences en masse. By compiling the millions of matches that players are making, and then feeding them into a sequencing algorithm, the project aims to build a higher-quality body of data that researchers could someday use to develop novel health or wellness treatments.

"At first glance, the match between user base and scientific problem seems unlikely. The fast-paced, first-person shooter-looter game filled with dark humor is primarily designed for gamers seeking adventure and action," wrote contributors on the project from McGill University, videogame science company Massively Multiplayer Online Science (MMOS) and Borderlands 3 developer Gearbox Studios in a recent nature biotechnology correspondence.

"But what could be a dead end turns out to be the strength of this initiative. A deployment in the Borderlands universe offers an opportunity to reach a public not particularly exposed to science, while at the same time it opens the door to a large and strong online community of players who can carry and amplify the impact of this initiative," they wrote.

Now nearly half a year in, Gearbox founder and CEO Randy Pitchford and MMOS cofounder and head of research and business development Attila Szantner tell MobiHealthNews that the output of Borderlands Science has far outstripped that of previous crowdsourced videogame research projects.

Not only have 1.6 million different players solved at least a single task, each completed an average of nearly 40 puzzles for a collective total of 63.2 million total puzzles solved – a stark increase in engagement over the 350,000-plus players and the five-task average logged by its predecessor, a standalone puzzle game called Phylo, over 10 years.

“I consider Borderlands Science a milestone project," Szantner told MobiHealthNews. "We have proven before that such integration works beautifully in a game where both the player community and ... the game are science oriented. Borderlands Science has proven that a citizen science feature in a mainstream shooter/looter with a diverse audience can be super successful, can bring enormous value to the game, and can be an empowering and fun experience to players, all while substantially contributing to scientific research."

A design and deployment unique from its predecessors

Borderlands Science benefits from a long heritage of citizen science projects, some of which embraced gamification design approaches to achieve their research goals, the team wrote in nature biotechnology.

These include Foldit, a puzzle game launched in 2008 to predict protein 3D structure; Stall Catchers, which has had participants review videos of mouse brain vessels to accelerate Alzheimer's disease research since 2016; and the aforementioned Phylo, developed by McGill researchers to map mammalian genes associated with diseases.

Other citizen science projects didn't ask much of their players, but instead require the hardware inside their game consoles.

“I remember using ‘Folding@Home’ on my PlayStation 3 and it inspired me," Pitchford told MobiHealthNews. "It was a non-interactive experience, basically crowd sourcing the computing power when the machines' owners were not using them, but it was not harnessing the brain power of the players themselves. When Attila came to me with his vision for tapping into the creativity and problem-solving ability of gamers, I got very animated and excited to help move the needle further.”

Szantner and MMOS's prior take on a citizen science research videogame was Project Discovery, which aimed to classify a large body of fluorescence microscopy images. Unlike other programs, Project Discovery was not released as a standalone game, but deployed within the sci-fi massive multiplayer online role-playing game Eve Online.

Project Discovery enrolled more than 300,000 people to participate, and saw an average engagement of more than 100 tasks completed per person. The team attributed that success to two major factors: the hundreds of thousands of active players who log into Eve Online every month, and the "more mature" demographic of its niche player base. (Eve Online's appeal is the simulation of a live economy with commodity trading and player-run corporations, and has a reputation among players as "spreadsheets in space.")

Designing for immersion and engagement

To expand upon this success, MMOS's next project would need to greatly increase the number of people exposed to a citizen science game by deploying within a more mainstream franchise. The challenge was doing so while maintaining engagement rates closer to Project Discovery than to Phylo.

"Although crowdsourced science projects in the past utilized gamification and even stand-alone mobile games that were built around solving scientific problems, our innovation was to take these citizen science tasks and integrate them with already existing major videogames and create seamless gaming experience," Szantner said. "This is a huge difference. Nobody has ever done it before, and so we were in uncharted territory.

"When doing such an integration, it is of utmost importance that this mini-game inside the larger game universe feels like an integral part of the experience. This is one way to ensure that we are not breaking immersion."

"When doing such an integration, it is of utmost importance that this mini-game inside the larger game universe feels like an integral part of the experience. This is one way to ensure that we are not breaking immersion."

Much of this immersion factor comes down to how the team chose to present Borderlands Science to its players, Szantner and Pitchford explained.

For starters, the mini-game is recorded in the player's journal as an optional quest provided by a scientist character who already plays a key role in the franchise's narrative. Once players interact with the flashy arcade machine, Gearbox introduces Borderlands Science's gameplay and real-world goals through an introductory video with a script that matches the cheeky and comedic tone of the franchise.

As for Borderlands Science itself, its artwork features the faces of Borderlands 3's protagonists and other franchise iconography, and is stylized with sounds, colors and image fidelity to match the 1980s arcade machine it's evoking.

This focus on player immersion is nothing new for the commercial videogame industry, which has spent years hammering out new technologies and best practices to help gamers lose themselves in a virtual world, Pitchford said. But, in a way, the design team was working against itself, since Borderlands Science also needed to compete with the shooting, driving and loot-hunting action of the main game.

With the goal of having at least 10% of the Borderlands 3 audience touch the mini-game in any capacity, the team again fell back on videogame industry staples: the loud, colorful arcade cabinet designs that for decades have separated players from their pocket change, and the promise of in-game boosters and cosmetic character outfits which have become more commonplace over the last several years.

Motivating players to try Borderlands Science for the first time was by far the biggest engagement hurdle for the project, Pitchford said. Once players got their hands on the colored blocks, he said, he had no doubt his designers could deliver a puzzle game that was worth replaying.

“With Borderlands Science, a lot of emphasis was placed on the design being, well, fun and engaging in its own right," Pitchford said. "It was important that the game itself was not a chore, but something that was stimulating and gratifying to interact with in and of itself. When success in this objective was combined with a deep integration with the themes, context and characters of the main Borderlands game, our customers embraced it.”

Participation in citizen science is a value-add for entertainment media

Parallel to the design challenges of Borderlands Science were the internal roadblocks that come with justifying any major project within a commercial organization. The development cost of Borderlands Science "was nontrivial" for Gearbox, and Pitchford said that he doesn't envision these types of projects directly driving profit through biopharma research partnerships or similar avenues.

"There was always a lot of friction against the commitment of time and energy from a commercial responsibility point of view," Pitchford said.

Instead, he advised those working at non-research commercial entities to be flexible on the scope and focus of any potential health research projects they may pursue, with Szantner adding that it's vital to win over internal leaders or champions who can push these projects along. But for the videogame or entertainment industry in particular, Pitchford and Szantner said that the strongest commercial argument for these projects is the unique value they can add to the final product.

For instance, early on the team discussed whether or not to present Borderlands Science as a straightforward mini-game to players with no mention of its research goals, but quickly decided that this sort of Trojan Horse approach would be a mistake. By being upfront about the project's scope, playing the game can become more rewarding and enjoyable for those interested in contributing their time to health research – a valuable bonus for those selling a videogame.

"The results have demonstrated that there is value to this kind of effort, not merely on the merits of the scientific value, but also on the commercial value," Pitchford said. "The fact that some of you reading these words today may not have heard about Borderlands before and will consider buying Borderlands 3 because of Borderlands Science creates a commercial case for other developers and publishers to put some of their energy toward efforts that have a good social component attached to them.”

That kind of value-add is only effective if the experience doesn't impose on the paying customer's entertainment experience, Pitchford warned. Here, he gave the example of attending a live stage performance, where following the entertainment some actors may walk around the crowd with a donation bin. Although charitable and often accepted, the reality is that the audience has already received the entertainment it paid for and is now being pressed for contributions, he said.

However, when that charitable request is instead incorporated into the entertainment in a way that is immersive and doesn't dilute the product, the entertainer is able to maintain their strong relationship with the paying audience – which for a videogame developer means that players will continue to purchase and engage with their releases.

“I think one of the reasons why Borderlands Science succeeds is because if players had no idea that the game they were playing was solving real-world scientific problems with sequencing microbial DNA, they would still be entertained by the experience and relate to how it is presented in the context of the larger Borderlands universe," Pitchford said. "I think caring for the interest of the customer must be a key component to success with integrating citizen science projects with commercial videogames."

Games and gamers as an untapped resource

Like other crowdsourced science projects before it, Borderlands Science taps the community to perform specific tasks at a massive scale. Since launch, its players have contributed each day what would be the equivalent of 10,000 to 15,000 hours of manual work. But even Borderlands 3's player base is only a fraction of the total market – according to the Entertainment Software Association, the videogame industry's largest trade association, more than 164 million adults in the U.S. alone spend their time completing challenges that rely on critical thinking and puzzle-solving skills.

For Szantner, leaving all of that unused computational power off the table is a missed opportunity for researchers.

“As people spend more and more time in the virtual worlds of videogames it is imperative that we find new ways to extract as much value from this time as possible," Szantner said. "I believe that we are only at the beginning of this journey, but what is certain is that the value is there."

What's more, this population may be especially primed for this type of work, Pitchford said. Players are already accustomed to receiving new instructions via gameplay tutorials and quickly applying their training to the problems ahead of them. Further, many boot up a videogame specifically seeking to tackle and overcome mentally taxing challenges, and receive gratification upon completing a task.

That type of flexibility and drive may deliver tangible benefits for experts mapping the human gut microbiome – or potentially other areas of research wrangling large quantities of data.

“My dream is that more and more games integrate citizen science into their projects, and that the collective skill and creativity of the billions of videogame players around the world can be pressed into the service of helping our species overcome some real-world scientific hurdles we are facing on the cutting edge of medicine, physics, engineering, climate, space exploration, and many other critical areas of focus," Pitchford said.

"As great as it will be to see actual work completed in Borderlands Science contributing to a real-world medical breakthrough, I think I would be just as happy with the idea of some other game having been inspired by Borderlands Science making the leap for us."

In addition to the data output of Borderlands Science, Pitchford hoped that the design considerations of the project and commercial videogames at large could be a positive influence on the budding field of health and medical software.

Engagement, for instance, has been a major obstacle for digital health apps over the years, with designers still hammering out the best ways to prevent user attrition, or even discern which engagement metrics are the most valuable indicators of therapeutic success.

While videogame makers have built an entire industry out of maximizing user engagement, Pitchford noted that he and his peers have benefitted from a relatively low-stakes environment in which to experiment and develop best practices.

As the healthcare industry begins to wade deeper and deeper into novel technologies, he encourages digital health stakeholders to think of interactive entertainment as a test lab and work with game designers to understand what approaches will be the most successful for patients.

"One of the beauties of videogames is that we can take risks on the cutting edge of simulation, artificial intelligence, user interface and so on; and on our very worst day, the worst we can do is not quite entertain someone as much as they like," he said.

"This affords us an interesting opportunity to take risks faster where the stakes are lower and along the way make discoveries of solutions that work. With the rigor of millions of gamers already having banged on a system, it can be applied to more consequential real-world endeavors.

"It’s very exciting stuff, and we’re just getting started on the potential that can be unlocked through better and better collaborations between digital interactive entertainment and the people tackling important challenges we must overcome in the real-world.”