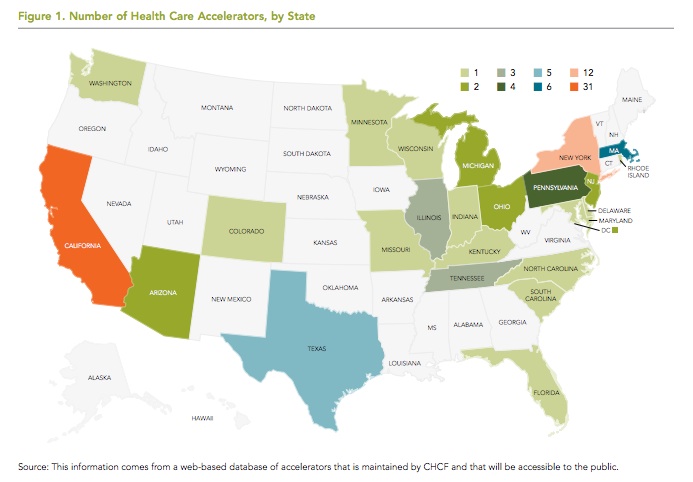

There are 115 dedicated healthcare accelerators worldwide, with 87 in the United States, according to a new report from the California HealthCare Foundation. The report, authored by Lisa Suennen, a prominent digital health investor who blogs under the name "Venture Valkyrie", includes university and corporate accelerators but doesn't count multiple sites (like Healthbox London and Healthbox Boston) as separate entities.

There are 115 dedicated healthcare accelerators worldwide, with 87 in the United States, according to a new report from the California HealthCare Foundation. The report, authored by Lisa Suennen, a prominent digital health investor who blogs under the name "Venture Valkyrie", includes university and corporate accelerators but doesn't count multiple sites (like Healthbox London and Healthbox Boston) as separate entities.

For the report, Suennen spoke with a number of stakeholders in the accelerator process including entrepreneurs, sponsors, and investors. She discovered that though the market is growing and evolving in a number of different ways -- most notably higher investment amounts from accelerators and more specialization -- there's also a widespread belief that there may be too many accelerators, churning out more companies than the market or the existing VCs can handle.

Suennen lays out six basic kinds of accelerator. The independent commercial model is the most familiar, consisting of groups like Rock Health or Startup Health. Because it takes time to see a return on the equity investments accelerators make in their startups, in order to be profitable, these organizations either need to find alternate revenue sources or work with sponsors -- often large healthcare corporations or VCs that support the companies as investments in possible future partnerships.

The second model, the enterprise-based innovation model, encompasses accelerators like those created by Sprint, Microsoft, Johnson & Johnson, or Boston Children's Hospital. These companies have ample resources, but they are investing very specifically in companies that can help support their core business. Even more specific are the accelerators in Suennen's third group, those organized around a particular product (Google Glass accelerator Glassomics) or a specialized market sector (Aging 2.0, which targets the aging care market).

Other groups are university-sponsored accelerators, which often don't take equity at all, economic development models, which are focused on improving the economy of a city or region, and partnership programs, which focus exclusively on matching up entrepreneurs with early partners, customers, and pilot testbeds.

The trend toward more funding, Suennen writes, is guided by the recognition that healthcare startups take longer to get off the ground and require more initial funding than many other types of startups, because of the extensive testing, validation, and, often, regulatory clearance they require. Various accelerators have moved from the once typical $10,000 to $25,000 per company to models that allow companies to get up to $500,000, either by giving up additional equity, or offering the money as follow-up money to companies that reach certain milestones.

Suennen walks through various models of assessing the success of an accelerator, recognizing that there's no consensus on how to best assess it. How much funding the companies have acquired since departing is a popular method, but it's easily skewed by one big success and doesn't account for the fact that plenty of companies raise lots of money and still, ultimately, fail. Job creation, pilots, and survival rates are all other metrics used by accelerators, but, Suennen points out, none of them are entirely convincing at such an early stage.

Indeed, most of the sponsors Suennen spoke with admitted that they didn't know if the accelerators they invested in really helped companies succeed. Some anonymously quoted sponsors in the report even complained that accelerators promoted repetitive ideas and an overcrowded marketplace which ultimately hurts the whole industry. She said most sponsors were involved for the networking and public relations value.

At the same time, the report suggests entrepreneurs themselves may be getting into accelerators for the wrong reasons. Most companies said they joined their accelerator to meet other healthcare companies, network, and build community, or else because being in an accelerator made them stand out in a crowded field. In addition, Suennen explores the phenomenon of accelerator junkies -- companies that move from accelerator to accelerator, subsisting on $20,000 investments and hemorrhaging equity, without ever raising a real seed round. There was no consensus on whether or not that model was a bad thing for the industry.

Finally, most stakeholders in the accelerator space agreed that some, if not many, of 87 US healthcare accelerators would start to die off as the relatively new space shakes out. Specialty accelerators are more likely to survive, as are longer and more intensive programs, programs with large capital investments, and models with a focus on collaboration, Suennen concludes from multiple interviews.