Focus group data from the Center for Health Care Strategies

Focus group data from the Center for Health Care Strategies

Digital health is one of the biggest areas of opportunity to help low income populations and, in the process, reduce costs for providers that treat Medicaid populations. But challenges hold it back, including available apps that aren’t up to snuff, and a system for validating digital health interventions that’s somewhat lacking. That was the consensus of panelists in a recent Commonwealth Fund webinar that built on a report the group published earlier this month.

Dr. David Bates, the chief innovation officer and senior vice president at Partners' Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, kicked off the discussion by sharing some preliminary data from research he and his team have conducted into the state of medical apps. His approach included a literature review, interviews with experts, a review of apps in the app store, and a usability study.

They identified a few hundred apps that targeted high-need, high-cost patients. Most of the apps displayed or recorded patient information, but only a few included reminders or alerts, guided the patient, or provided educational information. In addition, only 11 percent of the apps identified included both clinical experts and patients in their development process and only 22 percent rewarded the user in any way for achieving health goals. More concerning, Bates said, was the fact that only 33 percent of apps appropriately warned users in potentially dangerous situations.

“Our takeaways were that although apps have the potential to improve healthcare, they also have the potential to cause harm as they become increasingly integrated with the healthcare system,” he said. “And we did identify some cases in which, for example, patients could enter a very low blood glucose level and they did not get any notification that that was important. In other apps you could tell the app that you were suicidal and it wasn’t clear that anyone would be alerted.”

Rachel Davis, senior program officer at the Center for Health Care Strategies, spoke about patients who have multiple comorbidities as well as lifestyle complications like homelessness. She said these patients are disproportionately affecting Medicaid costs and are some of the most promising targets for digital health interventions.

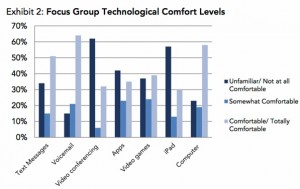

“We conducted a series of focus groups in 2013 with this population. And what we really wanted to do was get a sense of how comfortable these folks were with technology, what kind of technology they were using, and if they saw opportunities for technology to help them. Almost all of them owned a cell phone, a third of them owned a smartphone — and remember this was in 2013. They were fairly familiar with computers, they were comfortable with the internet, and they were able to articulate several areas where technology could help them manage some of the challenges they encountered.”

Specifically, the areas they identified included eligibility and coverage management, tracking of health records (often across multiple providers), lack of care coordination, medication management, and appointment management, which included both scheduling and remembering appointments and arranging transportation to make sure they reached them.

“Perhaps more than anything else we’ve seen out there, digital tools can help providers maintain contact with this population that can be very difficult to reach, and to proactively respond to health and social issues before crises appear,” Davis said.

Dr. Andrey Ostrovsky, who founded startup Care at Hand, talked about the main insight behind his company — that a lot of the care being provided right now to low income patients doesn’t come from doctors and nurses, but from nonclinical workers. By empowering these workers to alert the healthcare system to their hunches and observations about patients, provider systems can catch complications earlier and prevent readmissions.

Ostrovsky also spoke about the difficult position digital health startups are in right now when it comes to gathering enough efficacy data to become reimbursable.

“It’s a bit of a Catch-22,” he said. “We don’t have a very robust system in the digital health innovation ecosystem where companies can demonstrate preliminary results, and there aren’t enough opportunities to demonstrate preliminary data that’s viable. It’s basically either take the time to run a randomized control trial, which no investor would ever support, or you just pitch an idea and it’s all salesmanship.”

He believes nonprofit foundations could play a critical roll in filling that gap, in order to increase the number of quality, validated interventions available to providers.